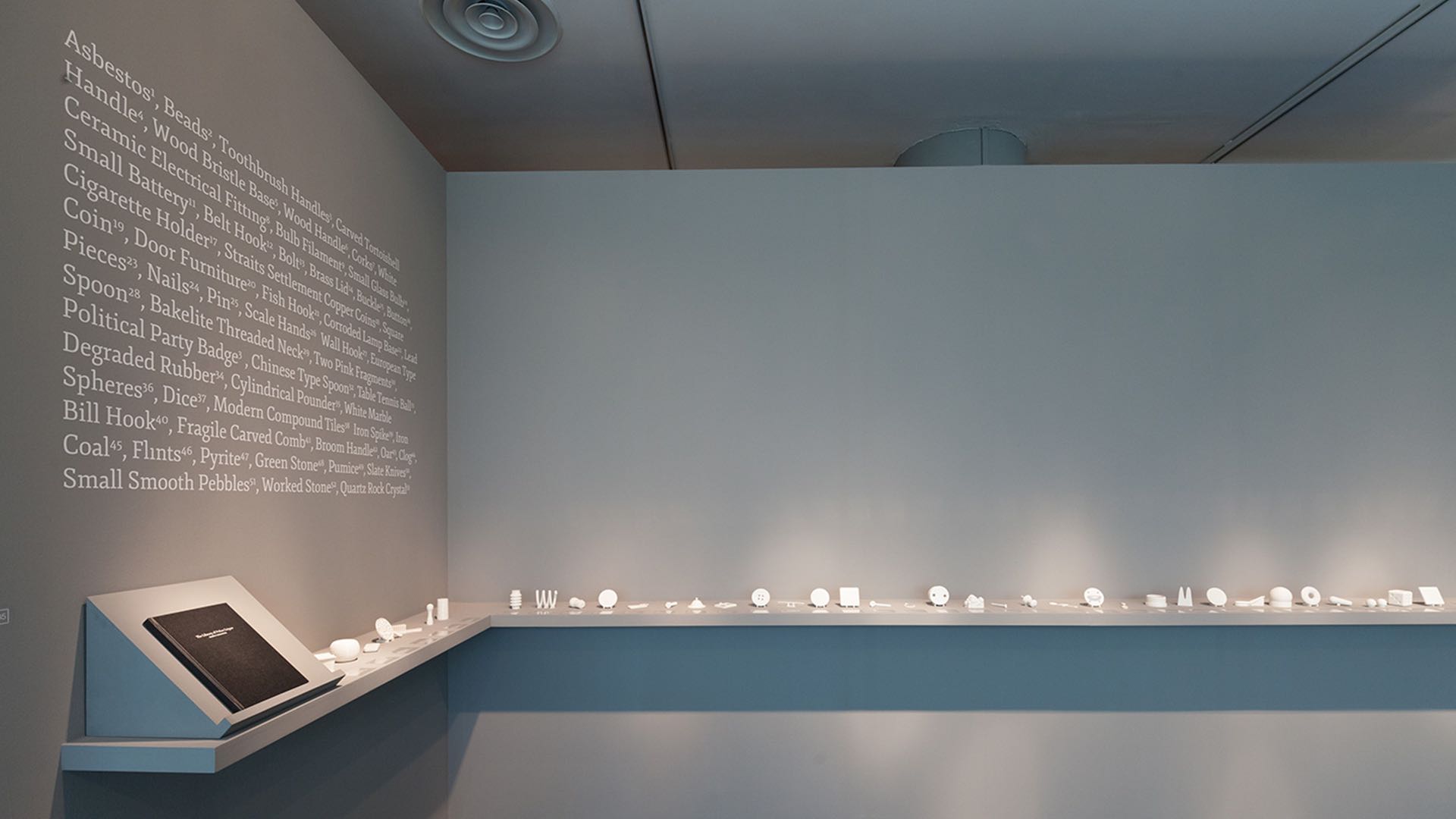

War Fronts

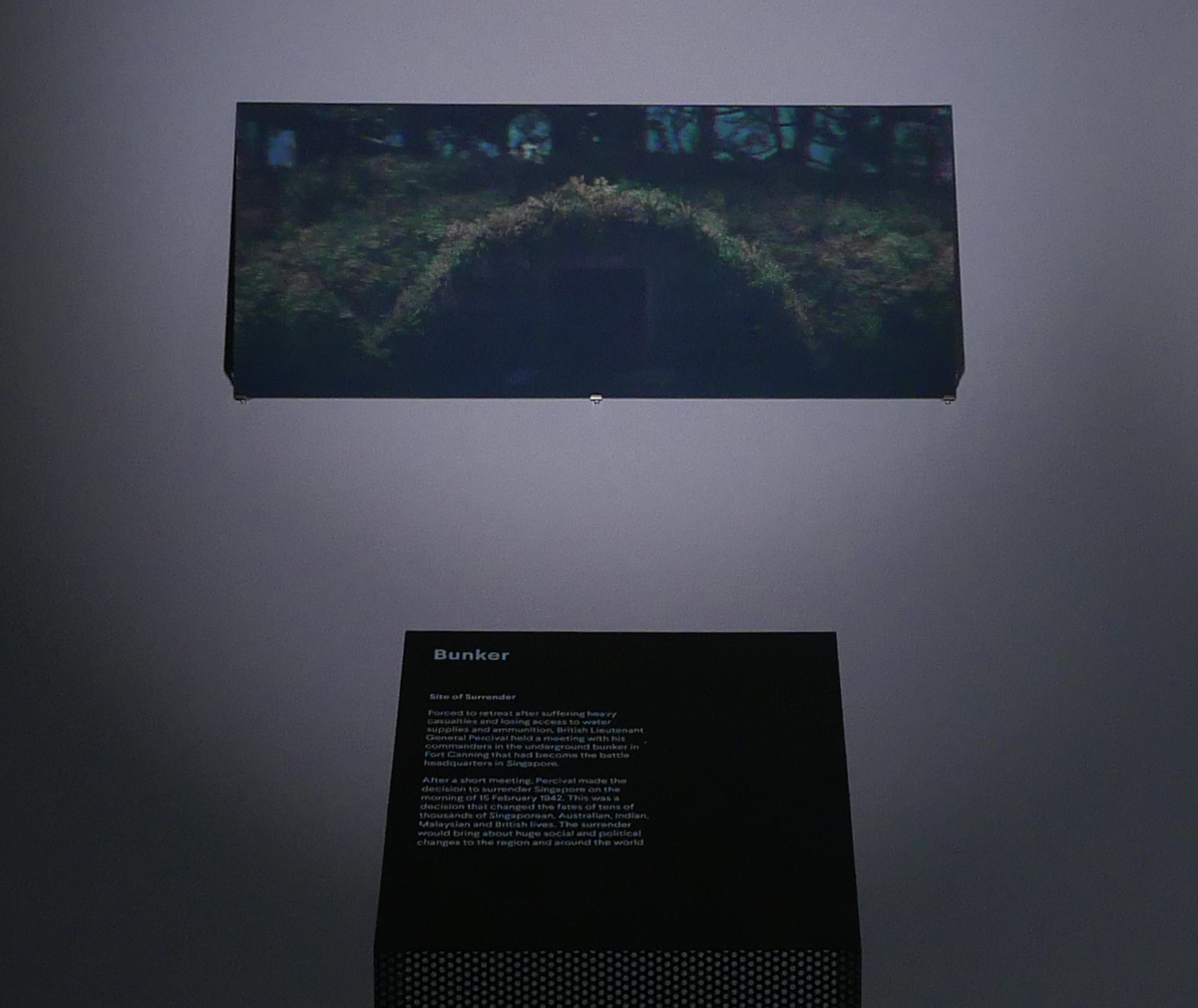

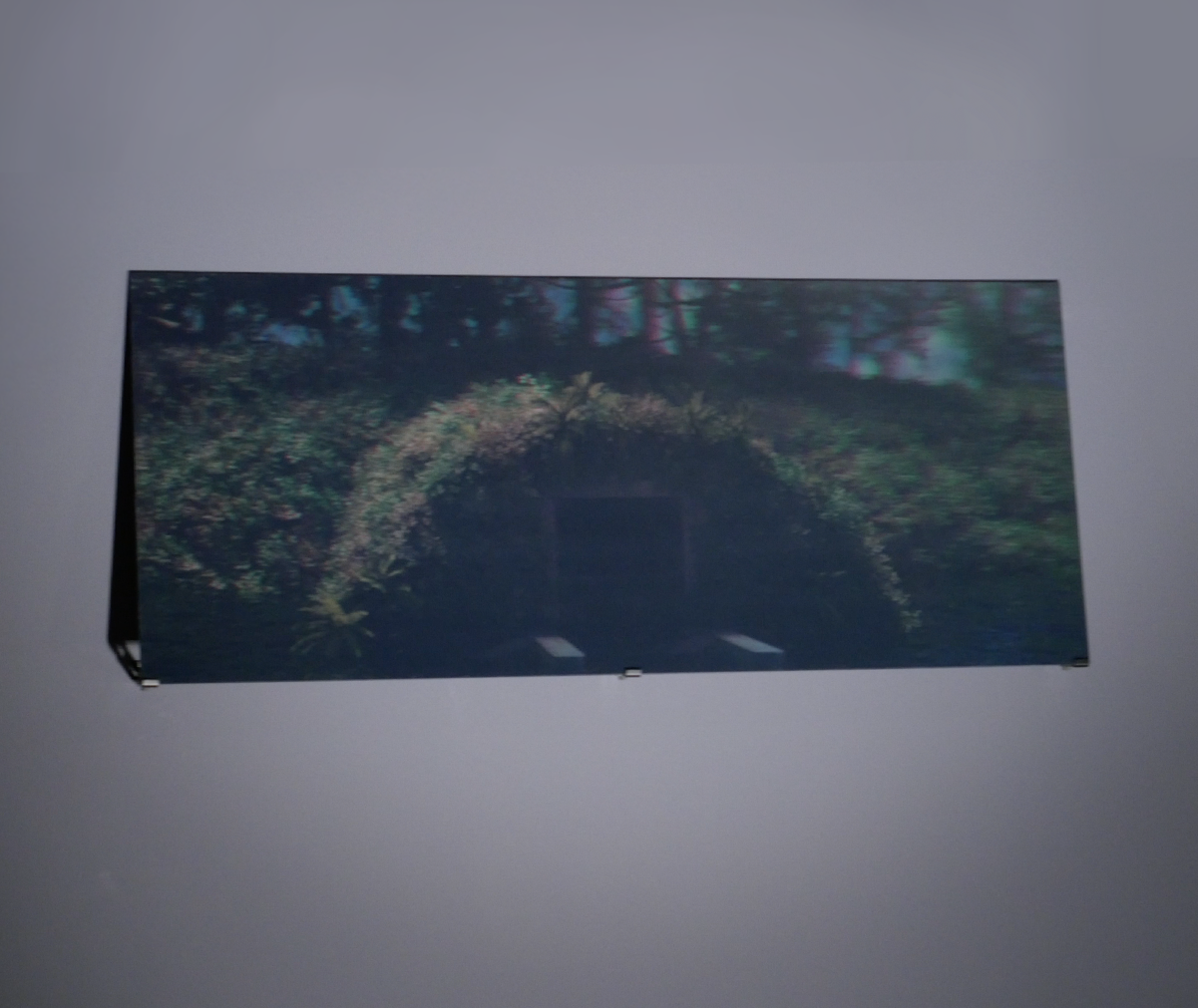

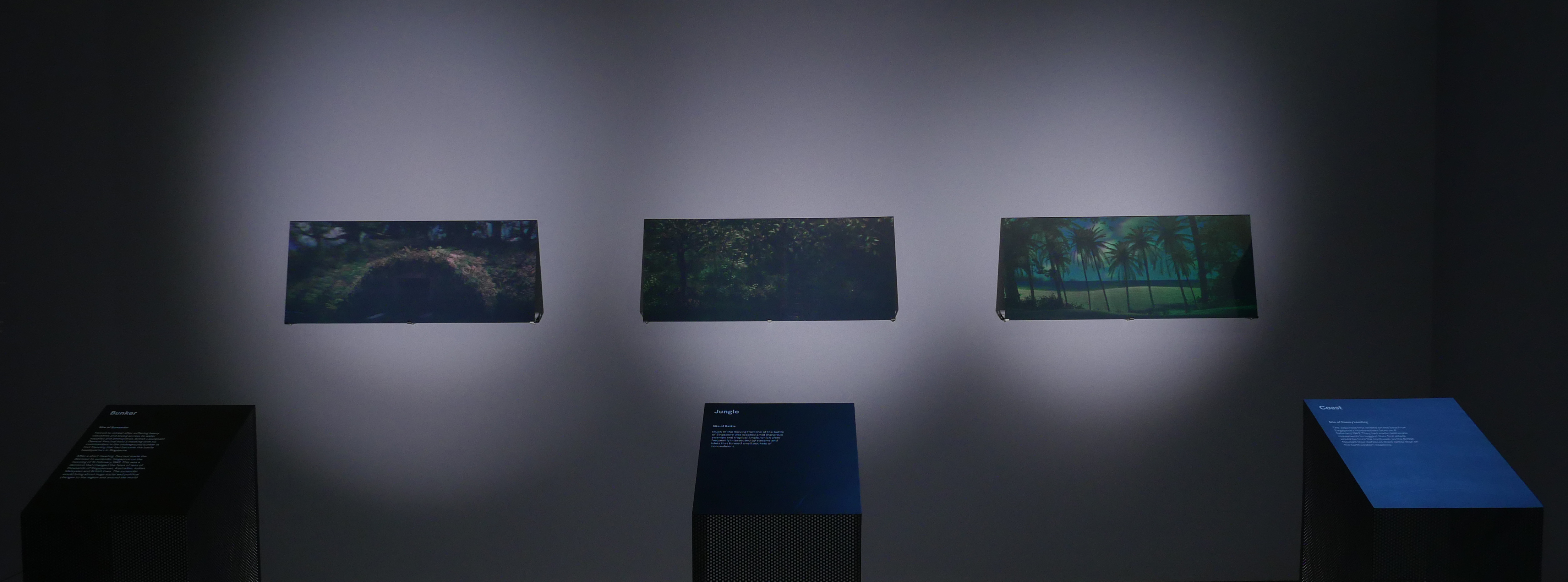

War Fronts is a series of three large-format landscape digital holograms depicting iconic World War II battlefronts in Singapore: the beach (site of enemy landing), the tropical jungle (site of battlefield), the concrete bunker (site of surrender). These are the three most iconic and identifiable wartime frontiers in Singapore: Singapore’s battle lines were drawn over places like these, and the “frontier” also delineates the limits of knowledge.

Historically, the depiction of landscape in art has often been motivated by ideological imperatives, whether as a means of articulating ideas of national identity, as social critique, or as a vision of a preferred future. Landscape can also be read as history, a landscape whose external appearance is the cumulative record of man in that place. The holograms force the viewer to continuously reposition themselves in order to reenact a physical search for war memories – searching the Singaporean landscape for traces of a history that cannot be seen or observed.

As a Singaporean, I've been thinking about the curious detachment I feel towards World War II as national war memory. When I visited World War II sites together with Angela and when we discussed our experiences, I noticed the contrast in my own personal response even more keenly. Where does this sense of emotional detachment from the WWII narrative come from? When I hear the oral history recordings made by Singapore’s WWII survivors, or see the photos and drawings made by Australian Prisoners-of-war held in Changi Gaol, I empathise with their stories and emotions, but I have difficulty comprehending the traumatic event as part of the imagined continuous timeline of ‘Singapore’.

Witnessing tens of thousands of Australians attend the solemn dawn memorial on Anzac Day at the Australian War Memorial on 27 Apri 2017, it seemed to speak of how the birth of the Anzac spirit and sense of unified Australian national identity were triggered directly by the events of WWI and WWII: the Australian during WWI and the Australian WWII.

I’ve been struggling to find a word to describe the “Singaporean during WWII”. Perhaps because Singapore’s national identity had not begun to exist during the years of 1942-1945, that makes it difficult to process the events of World War II as national experience and shared trauma.

Immediately after the war, war memorials and commemorations told overwhelmingly of specific memories of the war and POW camps – largely Chinese, Australian and British memories of the war.

It was only in the 1990s that there emerged a concerted push for more ‘inclusive’ WWII commemoration sites to equally acknowledge the stories of other ethnic minorities in Singapore - such as through the site of Bukit Chandu, which tells the story of the Malay Regiment which took a last stand against the Japanese before the fall of Singapore. It was fascinating to see that Bukit Chandu is framed today as a story of collective action / national participation, yet the agency of their action is framed as contributing to Singapore’s national identity, downplaying its significance as a story of Malay ethnic identity.

It appears that in trying to make the ‘national identity’ more inclusive, this has the unintended effect of blurring some of the finer details of individual ethnic narratives. For some, the depth, immediacy and intensity of emotion and grief felt over the suffering and trauma of World War II seems to have become fuzzy in the process of trying to find new words to retell these war stories.

In Benedict Anderson’s “Imagined Communities”, he describes the function of “ghostly imaginings” in the building of national identity, wherein living people continue to feel a strong connection with large numbers of the dead belonging to their national community. Through this, the idea of the nation is able to transcend time and the nation’s people can imagine themselves living out part of a larger continuous national story.

Because of the circumstances of history, and the high immigration levels and changes to Singapore’s demographic, we have needed to build a national identity based on our common existence in this place, rather than defining our national identity through recent shared traumas, or through the brave actions of ‘Singaporeans during WWII’.

I wanted to use a 3D imagining medium whose ability to carry symbolism is in doubt – to represent WWII as an event whose significance and impact has been so very different and diverse for people from different generations, communities and countries. I am interested in the changing symbolic value of war memory and the seemingly parallel path taken by the medium of holography – where the work can also exemplify what McLuhan speaks of as “the medium as the message”.

From historical illusion to technological illusion, from national aspiration to technological aspiration – faced with increasing detachment from reality, the holographic memory of war continues to expand in fiction and in our minds.

2017

Pulsed Laser Holography.

Commission for National Museum of Singapore and Australian War Memorial

Produced during an artist residency with the Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

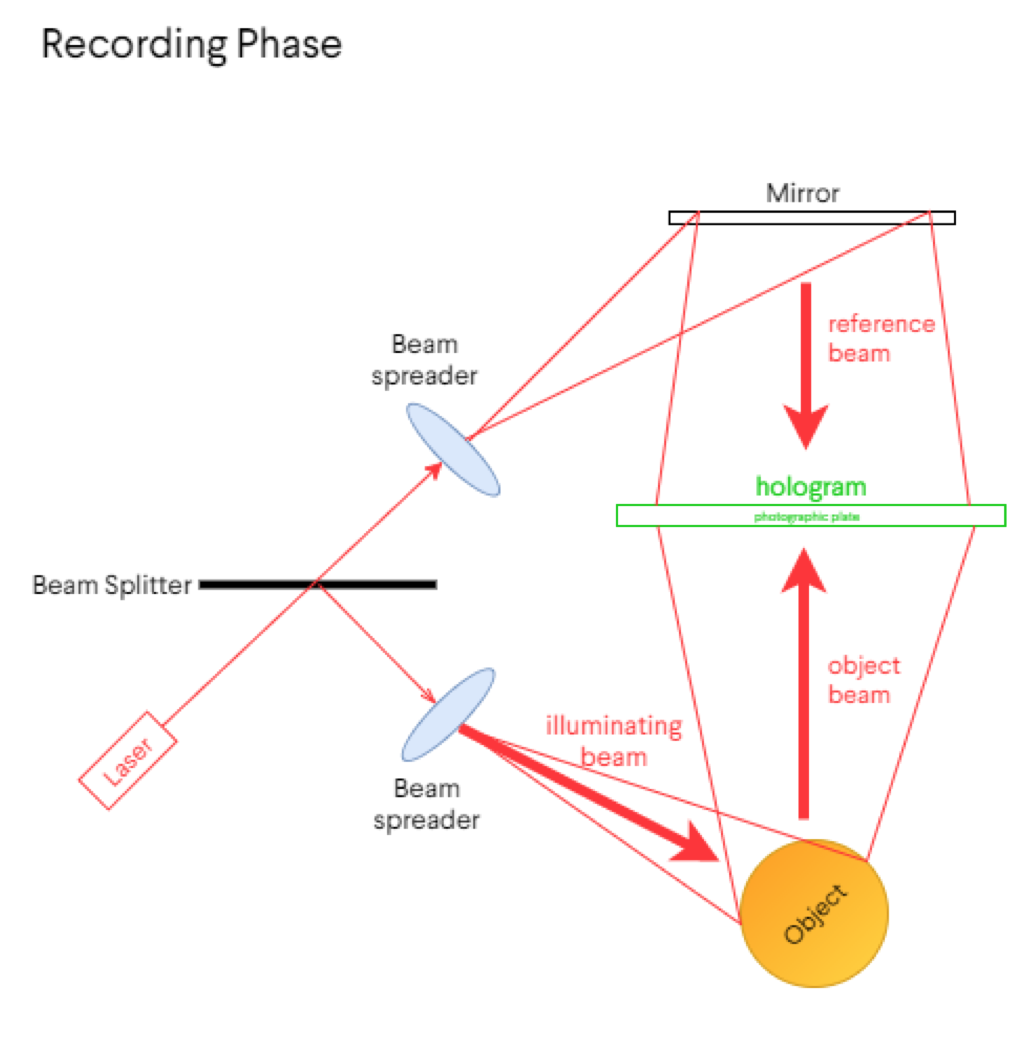

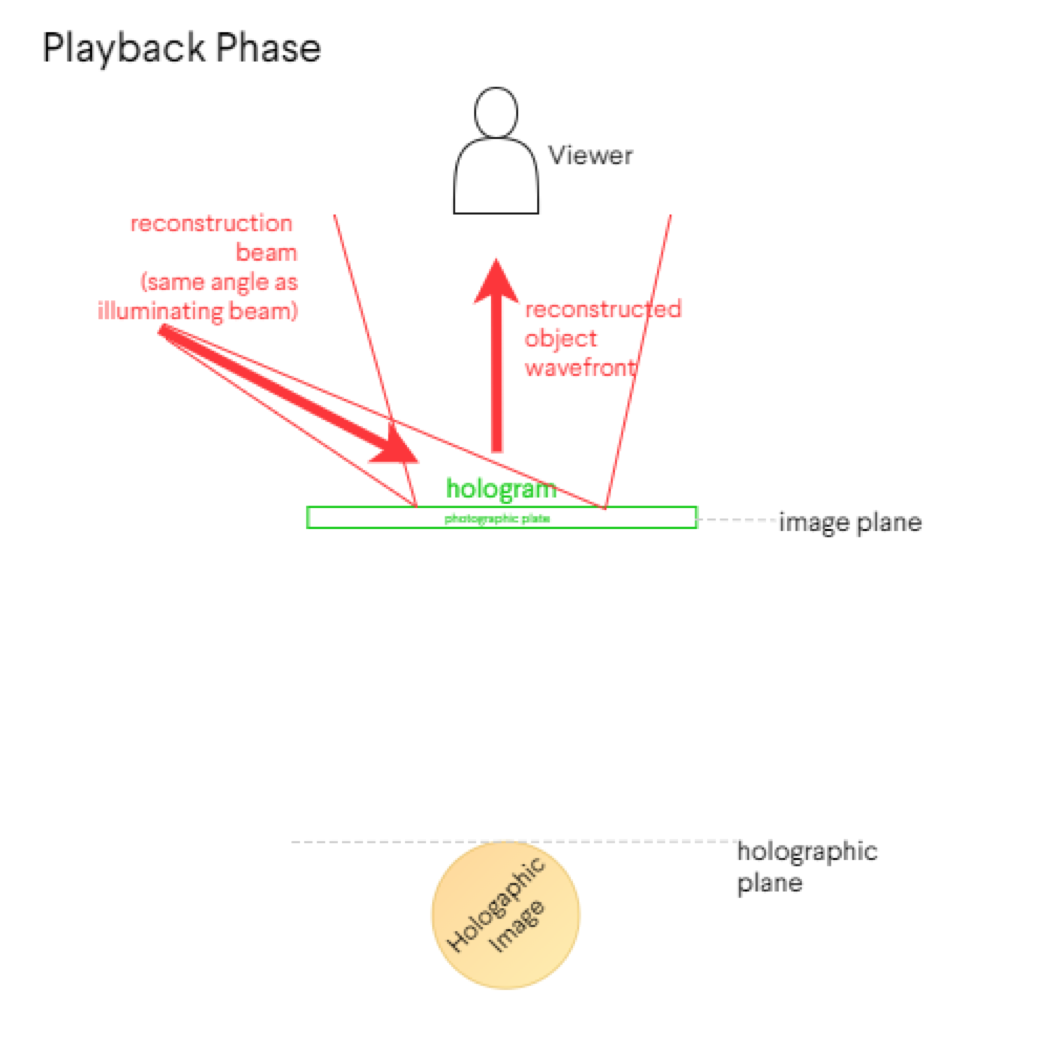

The hologram is a lens, or rather, an optical device that carries within it the ability to generate three-dimensional imagery (the holographic image) which sits detached on another plane beyond the image plane (the flat plane on which a photograph’s image exists).

During the recording of a hologram, a laser is used to provide a coherent source of light which is split into two - an object beam and reference beam. The object beam is widened with an expanding lens and reflected off the object and projected onto a photographic plate. The reference beam is also widened with an expanding lens and the light is made to shine back onto the photographic plate after reflecting off a mirror. The object beam and reference beam meet at the photographic plate and creates an interference pattern.

To see the holographic image of the object, a beam of light has to be positioned at the same angle as the illuminating beam used during the recording phase. When the hologram is lit, a virtual holographic image appears behind the image plane at the same position as the original object.

Although the underlying physics is well-known and widely understood by scientists and students of science alike, the hologram somehow remains largely misunderstood by the average layman. Since the hologram exists as a physical photographic plate, it is sometimes confused as an extension of photography, although a hologram is not at all like a photograph. A photograph is an image but the hologram is a lens through which we can see a 3D image. To complicate matters, today the word “hologram” is very loosely used to describe different kinds of visual effects and optical illusions such as magic lanterns, pepper’s ghost, rear projection, volumetric projection, lenticular prints, virtual reality. As a result, many do not know what a hologram really is.

For a moment in time, the hologram had seemed poised to be the successor to the photograph, with many fine art holography programmes developed in universities around the world including in Australia and UK between the 1970s and 1990s. But technical limitations in holographic image production at the time as well as unfavourable cultural and commercial conditions led to the flattening of the holographic image on both physical and symbolic level, resulting in total collapse of the holographic image to the image plane.

Although many technological advances have been made in the field of digital holography in recent years, today we still largely see holograms largely in flattened forms: as flattened embossings on credit cards, as rainbow patterns wrapped over surfaces, or broken up into glitter particles, continuously questioning the hologram’s very ability to carry symbolism. Over the years, three-dimensionality and then imagery was successively compromised, leaving only movement and colour behind. Even American electrical engineering professor Emmeth Leith, the co-inventor of three-dimensional holography, described his holograms as a “grin without a cheshire cat”. As hologram retailers struggled to build a consumer market they began aligning themselves with science museums and technology centres to try to capture national audiences on a mass consumption level. Ultimately this distanced the hologram further and further away from being a medium for narrative.

Despite having a premature demise in a commercial sense, the hologram still entered cultural consciousness as a medium designed for future mass consumption, in its disappearance from the public eye it transformed into a staple of science fiction films and books, and continues to expands in popular imagination.