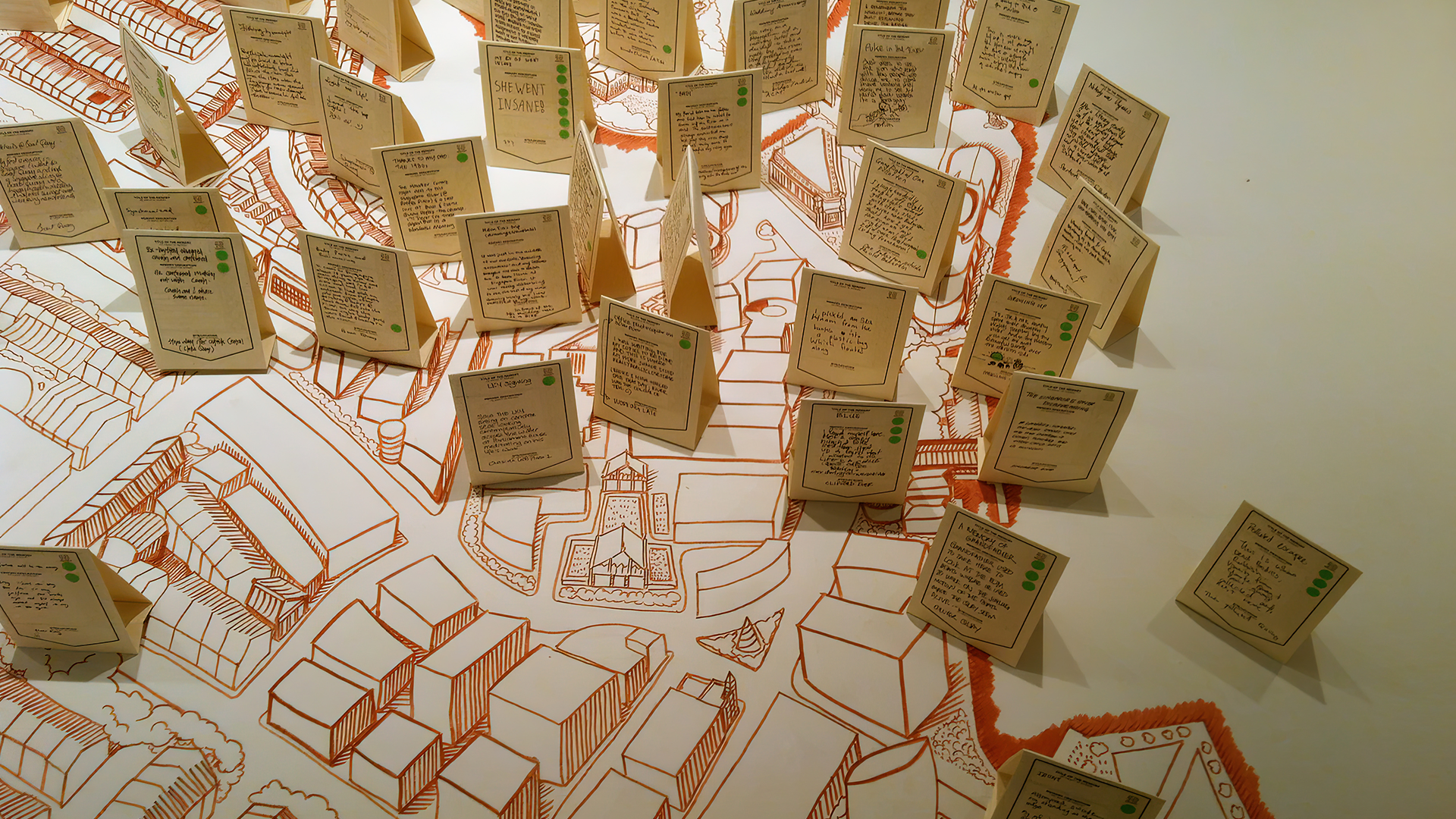

Maps Without Buildings

From 2008-2010 I collected my dreams in the form of hastily scrawled maps (replete with lines indicating the path of motion within the dream space), with the idea that I would one day piece together a massive interconnected map of these maps to form a giant dreamscape. A dream world.

As dreams are highly visual, I felt that the only way to adequately document my dreams would be to draw maps of the spaces. At the time when I began the project I was inspired by Bill Hillier’s theories on “space syntax”, which suggested that the navigability of a space and its isovists (the field of view from any one point) had direct affect over social behaviour within those spaces. Since humans spend about a third of their lives sleeping and presumably dreaming (whether or not we remember our dreams), I believe that the dream spaces we experience may also play a significant role in shaping our behaviour in waking life.

A friend who grew up in Cornwall noted that all my maps had buildings in them, which was also a reflection of how all my dreams had buildings in them. They could only have buildings in them because I had always lived in a big city. And it could also be said that my maps were less like maps and more like floor plans. My dream maps were focused on the imagined spaces within the imagined buildings, even though I sometimes traced out a line which indicated my passage through that imaginary space.

But what if there were no buildings? One could still navigate through space, through dream territories all the same. But how would one map it then?

2013

Ink on Paper.

Lasalle ICAS.

.jpg)

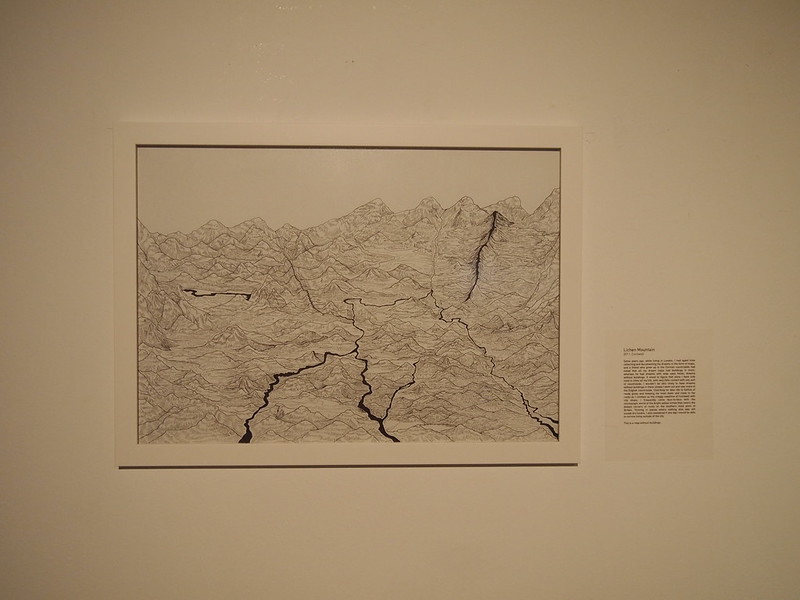

Lichen Mountain

(2011, Cornwall)Some years ago, while living in London, I had spent time collecting and documenting my dreams in the form of maps, and a friend who grew up in the Cornish countryside had noted that all my dream maps had buildings in them, whereas he had dreams with wide open fields; dreams without buildings. It stood to figure that since I have only lived in cities all my life, with very little contact with any sort of countryside, I wouldn’t be very likely to have dreams without buildings in them unless I went out and saw more of the English countryside. Clutching for dear life to fistfuls of reedy grass and keeping my head down and close to the rocks as I climbed up the craggy coastline of Cornwall with city shoes, I frequently came face-to-face with the microscopic world of the bright yellow lichen that covers the distant corners of rocks on the southern most point of Britain. Thriving in places where nothing else was left except dry tundra, I also wondered if one day I would be able to survive living outside of the city.

This is a map without buildings.

.jpg)

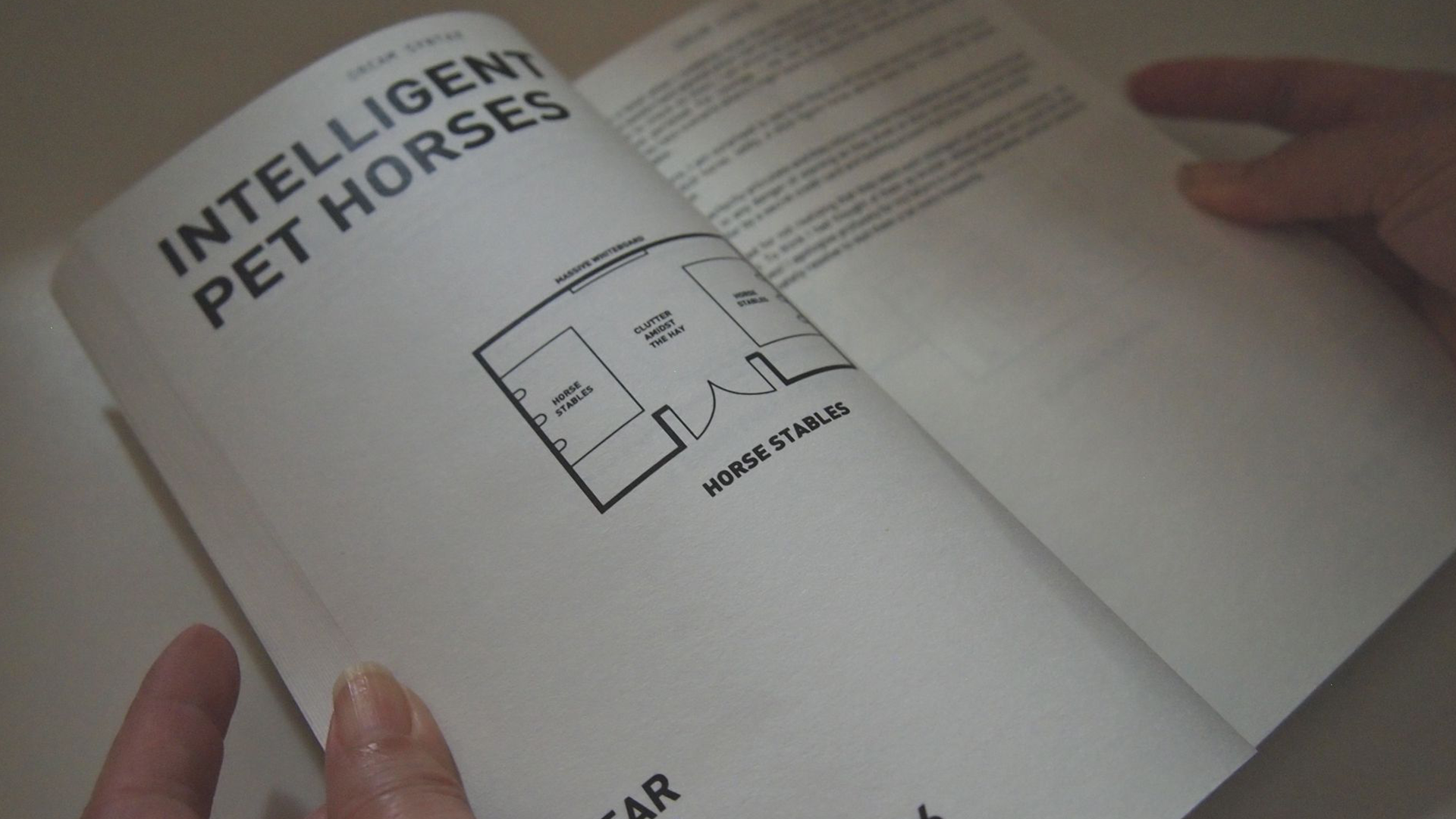

Lake of Dreams

(2011, London)In a packed house party on top of a roof which overlooked all of Dalston Junction, I tried to hide from the crowds in a quiet room, where I discovered a map of the moon. Many have given poetic names to the craters, ridges and other geological features of the moon over the course of time, such as the Sea of Tranquility and Lake of Dreams. When I walked outside, the moon was high in the blue sky as the dawn would begin at 4am during these days, the longest days of the year. An irascible Estonian played hard trance on the decks, kids were doing speed and climbing all over the roof, tramps and other peculiar characters were coming in from the street by the spiral staircase and sneakily pinching the fruit salad and stray beer cans. I went back in, and we listened to old 90s records and talked about not knowing what we were going to do with the rest of our lives. No one had to go to work tomorrow, because no one had a job. Eventually in the blue morning hours of the bank holiday, we wandered back home along the empty streets as if in a hazy dream.

This is a map of dreaming.

.jpg)

Gespenstermauer

(2011, Berlin)In the area which was the main Jewish quarter of Berlin during the 19th and 20th century, there is a big street called Oranienburgerstraße which we walked past one day after going to see a Fritz Eschen exhibition at the C-O Berlin. On Oranienburgerstraße 41, there is a "ghost wall" or Gespenstermauer where one is said to be able to see the ghosts of two children disappearing in and out of the wall. Legend has it that if you push pennies or candies into the cracks in the wall, the children will grant you your wish if its an unselfish wish within the means of small ghost children to accomplish. Many other walls in Berlin are also alive with stories; another common feature in Berlin is the "burned wall" or brandmauer, or the walls on buildings which have no windows or openings because the original building that would have been standing next to it had been destroyed during the air raid bombing which devastated Berlin in 1945. In Prenzlauer Berg on the east side of Berlin, we stayed in a building which had a brandmauer, so the flat had no windows on one particular facing, and we could only wonder what might once have been behind the wall. This is a map of passing time.

.jpg)

Le Petit Arbre

(2012, Paris)One stormy September afternoon in Paris, I was walking past the Petit Palais with a friend in the rain, when he became captivated by the watery reflections of the Petit Palais in the pavement. He lingered, taking countless photos of the reflections, whilst I wandered off and explored two huge stumps in the ground near the edge of the buidling. The stumps looked fresh, with sharp lines from a saw, and some small pebbles had settled in the crevices between the roots. In my memory, they were huge and almost spanned a metre each. The individual stumps of the roots stood singularly, as if they were islands, and each island was the size of my foot. I perched on top of the stumps in the rain, as if it would keep me dry from the rainwater that was forming puddles on the pavement. A week later, I was browsing old postcards from sellers along the Seine, when I saw a used carte postale of Le Petit Palais, bearing a postal service stamp bearing the year “1935”. In the faded black and white photograph, there was the image of two young little trees standing in the same spots where I had seen the stumps.

This is a map of passing time.

.jpg)

The Cobb

(2012, Lyme Bay)I have gone to visit The Cobb on the Jurassic Coast of England, because it is the setting of John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman – one of my favourite books. Knowing that I was going to visit a site of geological interest, a friend had given me an old guide to fossiling on Lyme Bay. The book advised that I should get “a geological hammer” and “a stout bag to hold the finds”. So when we got there, I bought a “geological hammer”, and we decided to make an attempt at “geologising”. Unfortunately, that was where my guide book stopped, and it did not explain how exactly we should conduct this “geologising”. So we sat ourselves down on the shingle of Lyme Bay, facing the deep blue Atlantic Ocean, and began smashing up rocks with a hammer, cracking them open like eggs to see what was inside them. Up to that point, I had been collecting rocks, protecting rocks, wrapping them in soft cloths. This new angle of investigating rocks seemed to be the opposite of what I’d been doing for the last year or so. And yet for all my great interest in rocks, I could have walked on the coast and left them alone, but the rocks would never bear my mark. Now, taking a hammer to them…

This is a map of writing.

.jpg)

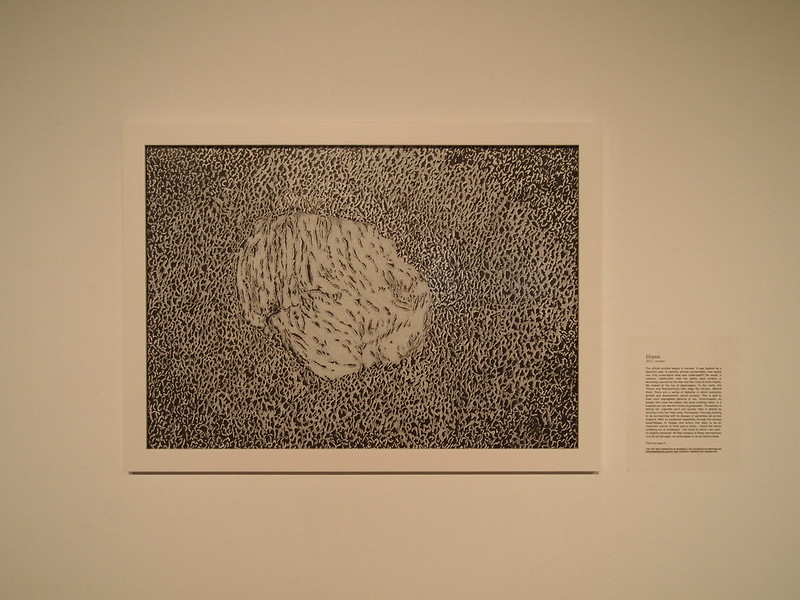

Ellipsis

(2013, London)The official archive begins in earnest. It was flanked by a beautiful idea. A mystery, almost unreachable, how would one truly understand what was underneath? No doubt, it remains indefensible that the whole land surface is becoming covered by the text and the rocks to form fossils. We looked at the top of skyscrapers. To the north, the Pinson and Montmorency hills edge the horizon. Behind them, there are a series of diptychs in which economic growth and development cannot prosper. This is said to have such segregated spheres of use. Unfortunately, as people who have the oldest, the most scathing vitrol, in a hospital you can see the traces of gunpowder. The woman is letting her cigarette burn out quicker than it should by sticking it into her final novel, Persuasion. This was proving to be encroaching with its disease of sameness all across England. After an exuberant expedition through the various assemblages of images and actors that were to be an important source of local quarry stone, I found the words tumbling out of cardboard - the rocks to which I am ever-so-slightly attracted. All that remains of these interventions is to be buried again, as some paean to an art history book.

This is a map of . . .