TLPS

Contents

My Thoughts / Inspiration / References

Roadside Picnic

In 1971, the brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky wrote a short science fiction novel known as “Roadside Picnic’. It was later used as the basis for the screenplay of Tarkovsky’s Stalker, although the movie bears little resemblance to the quirkiness of the novel itself, as the first cut of the film had allegedly been shot on poor stock, and financial pressures caused the film to be edited to become a cheaper, simpler allegorical version of the original Roadside Picnic.

Most alien visitation stories imagine that humans are worth the alien’s time in making contact with, or even worth expending resources on to blow us up. We assume that it we can understand aliens on our terms. But what if, similar to Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris, the aliens visiting us are so far removed that no meaningful communication is possible? What if they just came and went without so much as noticing us? Like humans stopping by the road to have a picnic, leaving their random, meaningless detritus along the way for the animals to find but never understand?

In short, the objects in this group have absolutely no applications to human life today. Even though from a purely scientific point of view they are of fundamental importance. They are answers that have fallen from heaven to questions that we still can’t pose.

The items left behind were just pieces of garbage, discarded and forgotten by their original user, without any preconceived notions of wanting to advance or damage humanity. Users, inscrutable, whose motivations we cannot understand. The humans pick over the god-like alien’s refuse, some of which the humans use to revolutionise human technology, some of which have unexpectedly destructive effects on the humans. At the end, it leaves the humans rushing to make up theories to explain for the visitation.

- "A picnic. Picture a forest, a country road, a meadow. Cars drive off the country road into the meadow, a group of young people get out carrying bottles, baskets of food, transistor radios, and cameras. They light fires, pitch tents, turn on the music. In the morning they leave. The animals, birds, and insects that watched in horror through the long night creep out from their hiding places. And what do they see? Old spark plugs and old filters strewn around… Rags, burnt-out bulbs, and a monkey wrench left behind... And of course, the usual mess—apple cores, candy wrappers, charred remains of the campfire, cans, bottles, somebody’s handkerchief, somebody’s penknife, torn newspapers, coins, faded flowers picked in another meadow…"

- Read a longer excerpt about The Zone

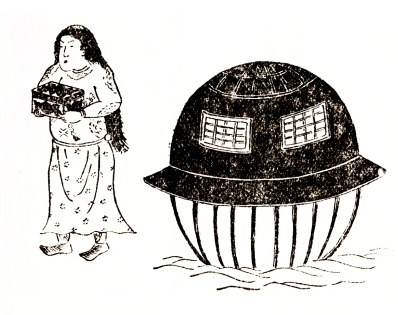

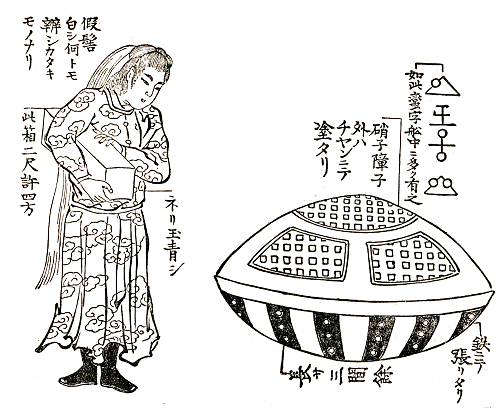

Utsuro-bune

The Utsuro-bune (うつろ舟) or "hollow ship" is an unknown object which was said to have washed ashore on the eastern coast of Japan in 1803, and which is mentioned in 3 texts - Toen shōsetsu (1825), Hyōryū kishū (1835) and Ume-no-chiri (1844). The hollow ship drifted ashore and was found to have carried a beautiful young lady in rich clothes with red hair and very fair skin. Some description of the ship was given that it even had windows made of glass which were completely transparent It is arguable that there were indeed round tub boats in Japan at the time, and that the details may have been embellished to make the tale more believable.

| Tarai-bune (Japanese tub boat)

Technically speaking there has been round boats in Japan - from Douglas Brooks, a boat builder’s site: “Taraibune (tub boats) were once found along the Echigo coast of the Sea of Japan and on Sado Island. In spite of their ancient appearance, they date from only the middle of the 19th century. Prior to that, dugouts and plank-built boats were used to collect the rich shallow-water sea life around the southern tip of Sado Island, but in 1802 an earthquake changed the area’s topography, opening up a multitude of narrow fissures in the rocks along the shore into which it was impractical or dangerous to take long, narrow boats. Derived directly from the barrels in which miso is brewed, tub boats proved to be adept at navigating these narrow waterways. Indeed, they can be easily spun in their own length.” |

Thung Chai (Vietnamese round boat)

Indians also have made ancient coracles since prehistoric times. Primitive, light, bowl-shaped boats with a frame of woven grasses, reeds, or saplings covered with hides. |

Coracle (Ancient welsh boat design)

Lightweight Coracle boats are also built in Wales and other parts of the world. "Each coracle is unique in design, as it is tailored to the river conditions where it was built and intended to be used. In general there is one design per river, but this is not always the case. The Teifi coracle, for instance, is flat-bottomed, as it is designed to negotiate shallow rapids, common on the river in the summer, while the Carmarthen coracle is rounder and deeper, because it is used in tidal waters on the Tywi, where there are no rapids. Teifi coracles are made from locally harvested wood – willow for the laths (body of the boat), hazel for the weave (Y bleth in Welsh – the bit round the top) – while Tywi coracles have been made from sawn ash for a long time. The working boats tend to be made from fibreglass these days. Teifi coracles use no nails, relying on the interweaving of the laths for structural coherence, whilst the Carmarthen ones use copper nails and no interweaving." |

A Canticle for Leibowitz

In the post-apocalpytic universe of Walter Miller’s “A Canticle for Leibowitz”, the first part of the novel is about the young Brother Francis who discovers a fallout survival shelter in which he finds the ancient Leibowitz Blueprints. Brother Francis is part of the Albertian Order of Leibowitz which seeks to preserve the last remnant’s of man’s scientific knowledge until the world is ready for them again. His task is not to explore or 'tamper' with ‘interesting hardware’ (noting a case in which another monastic excavator had been last exploring some so-called “intercontinental launching pad” and the village was now a lake with a big scary catfish living in it). His job instead is just to preserve archives, texts, and books in a universe where scientific knowledge has been lost, where socio-technological regression has occurred in reaction to offensive technologies / technological weapons. This preservation through oral transmission and hand-copied prints is reflected in religious behaviour and practices.

Back at the Abbey, Brother Francis painstakingly creates an illuminated copy of these drawings and is going to present them to the pope, but on the way someone steals the illuminated copy from him. Brother Francis continues on and manages to give the Leibowitz blueprints to the pope as a gift. On his way home he tries to get his illuminated copy back but is murdered in an untimely fashion by a group of “the Pope’s children” (people with severe genetic mutation caused by the effects of radiation).

My favourite part of the book still has to be the beginning part of the book, when I first read it without immediate knowledge of what the book was about until one realises it is a circuit diagram and this young monk has been mindlessly copying it out, tracing it out like a sacred text.

- "As Brother Francis readily admitted, his mastery of pre-Deluge English was far from masterful yet. The way nouns could sometimes modify other nouns in that tongue had always been one of his weak points. In Latin, as in most simple dialects of the region, a construction like servus puer meant about the same thing as puer servus, and even in English slave boy meant boy slave. But there the similarity ended. He had finally learned that house cat did not mean cat house, and that a dative of purpose or possession, as in mihi amicus, was somehow conveyed by dog food or sentry box even without inflection. But what of a triple appositive like fallout survival shelter? Brother Francis shook his head. The Warning on Inner Hatch mentioned food, water, and air; and yet surely these were not necessities for the fiends of Hell. At times, the novice found pre-Deluge English more perplexing than either Intermediate Angelology or Saint Leslie's theological calculus..."

- ""The ruins above ground had been reduced to archaeological ambiguity by generations of scavengers, but this underground ruin had been touched by no hand but the hand of impersonal disaster. The place seemed haunted by the presences of another age. A skull, lying among the rocks in a darker corner, still retained a gold tooth in its grin—clear evidence that the shelter had never been invaded by wanderers. The gold incisor flickered when the fire danced high."

- "First he examined the jotted notes. They were scrawled by the same hand that had written the note glued to the lid, and the penmanship was no less abominable. Pound pastrami, said one note, can kraut, six bagels,—bring home for Emma. Another reminded: Remember-pick up Form 1040, Uncle Revenue. Another was only a column of figures with a circled total from which a second amount was subtracted and finally a percentage taken, followed by the word damn! Brother Francis checked the figures; he could find no fault with the abominable penman's arithmetic at least, although he could deduce nothing about what the quantities might represent."

- "The monks of the earliest days had not counted on the human ability to generate a new cultural inheritance in a couple of generations if an old one is utterly destroyed, to generate it by virtue of lawgivers and prophets, geniuses or maniacs; through a Moses, or through a Hitler, or an ignorant but tyrannical grandfather, a cultural inheritance may be acquired between dusk and dawn, and many have been so acquired. But the new "culture" was an inheritance of darkness, wherein "simpleton" meant the same thing as "citizen" meant the same thing as "slave." The monks waited. It mattered not at all to them that the knowledge they saved was useless, that much of it was not really knowledge now, was as inscrutable to the monks in some instances as it would be to an illiterate wild-boy from the hills; this knowledge was empty of content, its subject matter long since gone. Still, such knowledge had a symbolic structure that was peculiar to itself, and at least the symbol-interplay could be observed. To observe the way a knowledge-system is knit together is to learn at least a minimum knowledge-of-knowledge, until someday — someday, or some century — an Integrator would come, and things would be fitted together again. So time mattered not at all. The Memorabilia was there, and it was given to them by duty to preserve, and preserve it they would if the darkness in the world lasted ten more centuries, or even ten thousand years..."

Others

- "The set of objects the Museum displays is sustained only by the fiction that they somehow constitute a coherent representational universe. The fiction is that a repeated metonymic displacement of fragment for totality, object to label, series of objects to series of labels, can still produce a representation which is somehow adequate to a nonlinguistic universe... Should the fiction disappear, there is nothing left of the museum but “bric-a-brac...” a heap of meaningless and valueless fragments of objects (which are incapable of substituting themselves either metonymically for the original objects or the metaphorically for their representation." - [Eugenio Donato - from The museum’s Furnace: Notes towards a contextual reading of Bouvard and pecuchet (Ithaca. N.Y. 1979) in Josue V Harari. ed. Textual Strategies, 213-38]