ABOUT THE WORK

From Dust to Dust

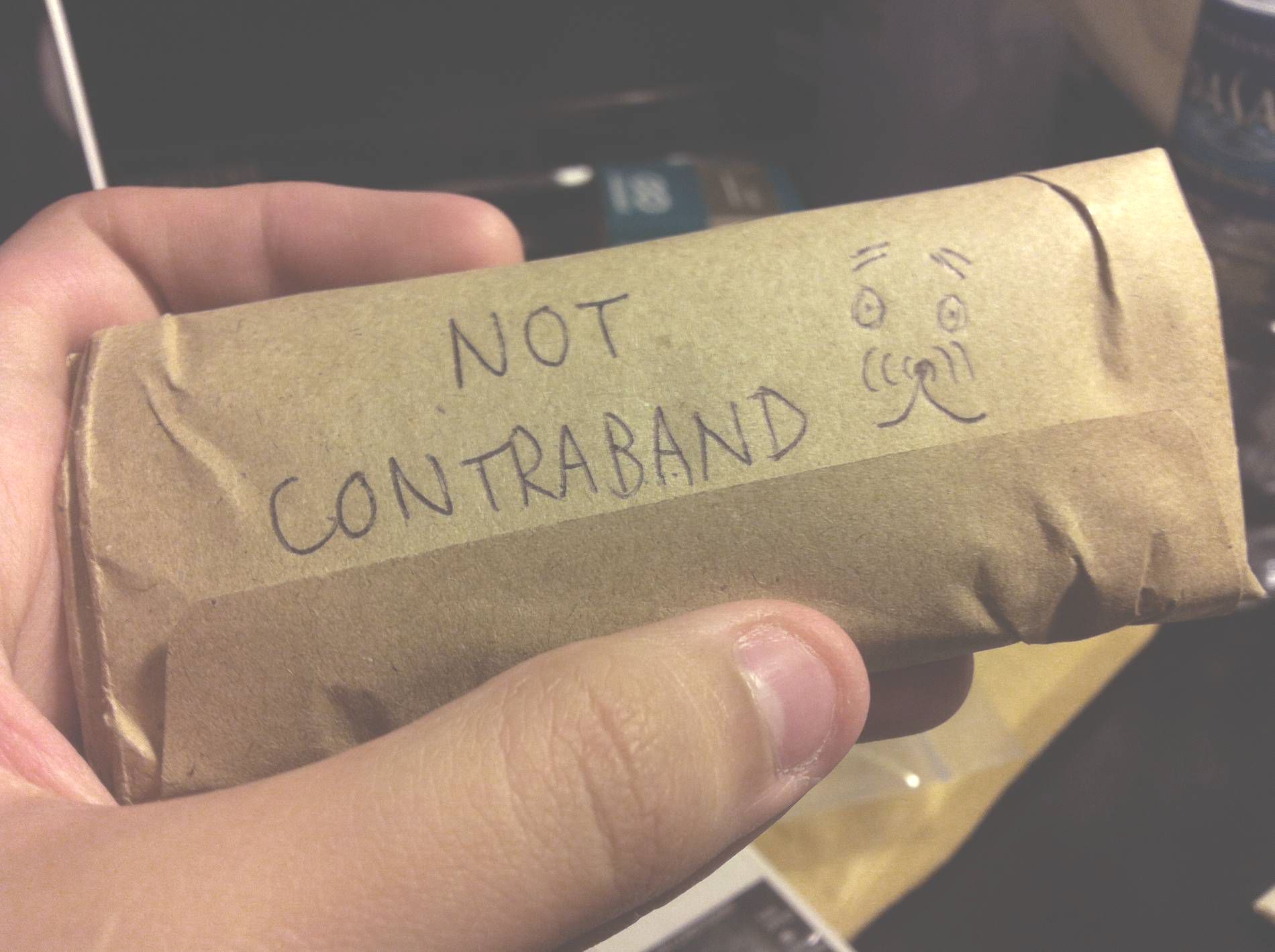

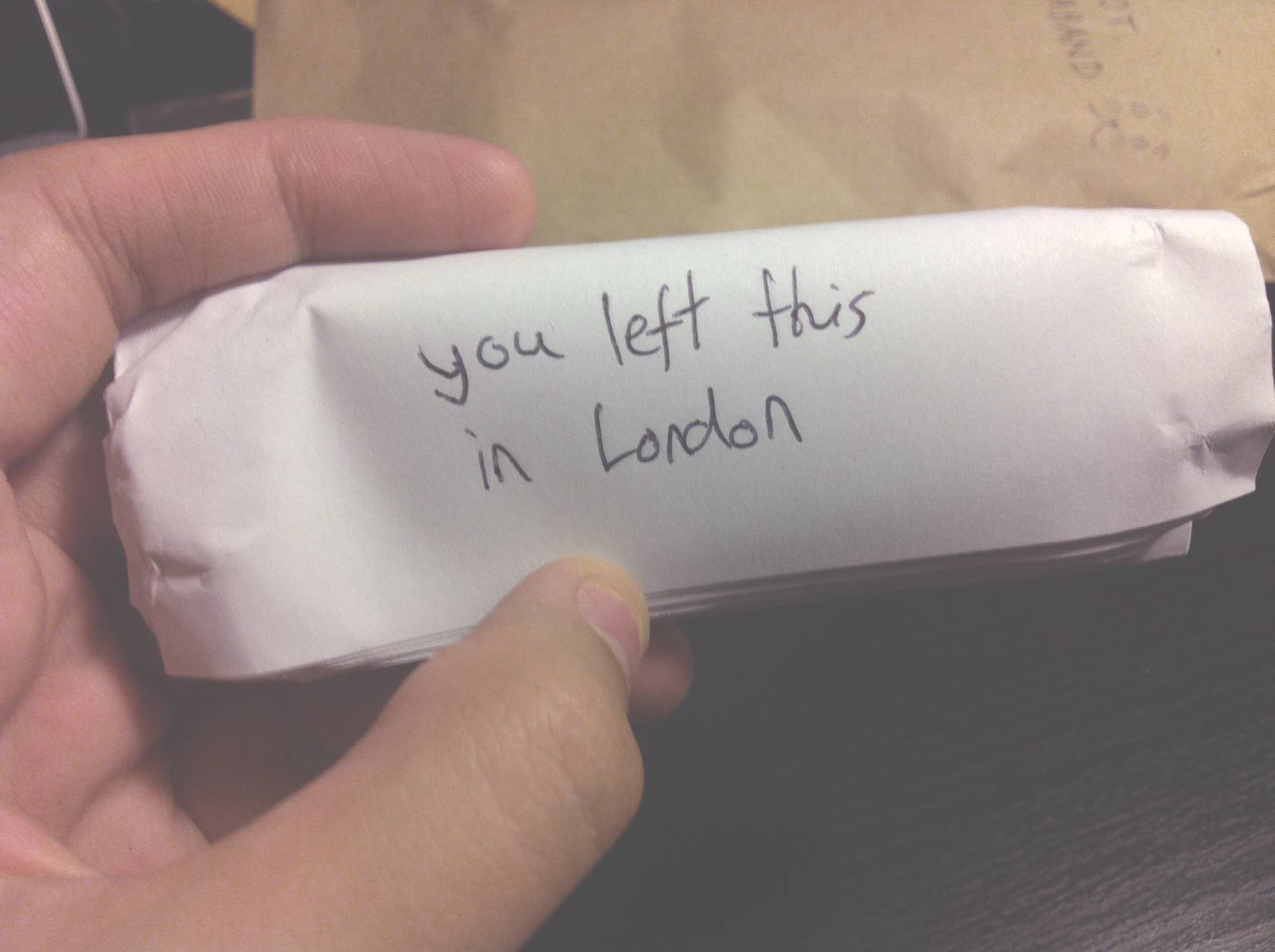

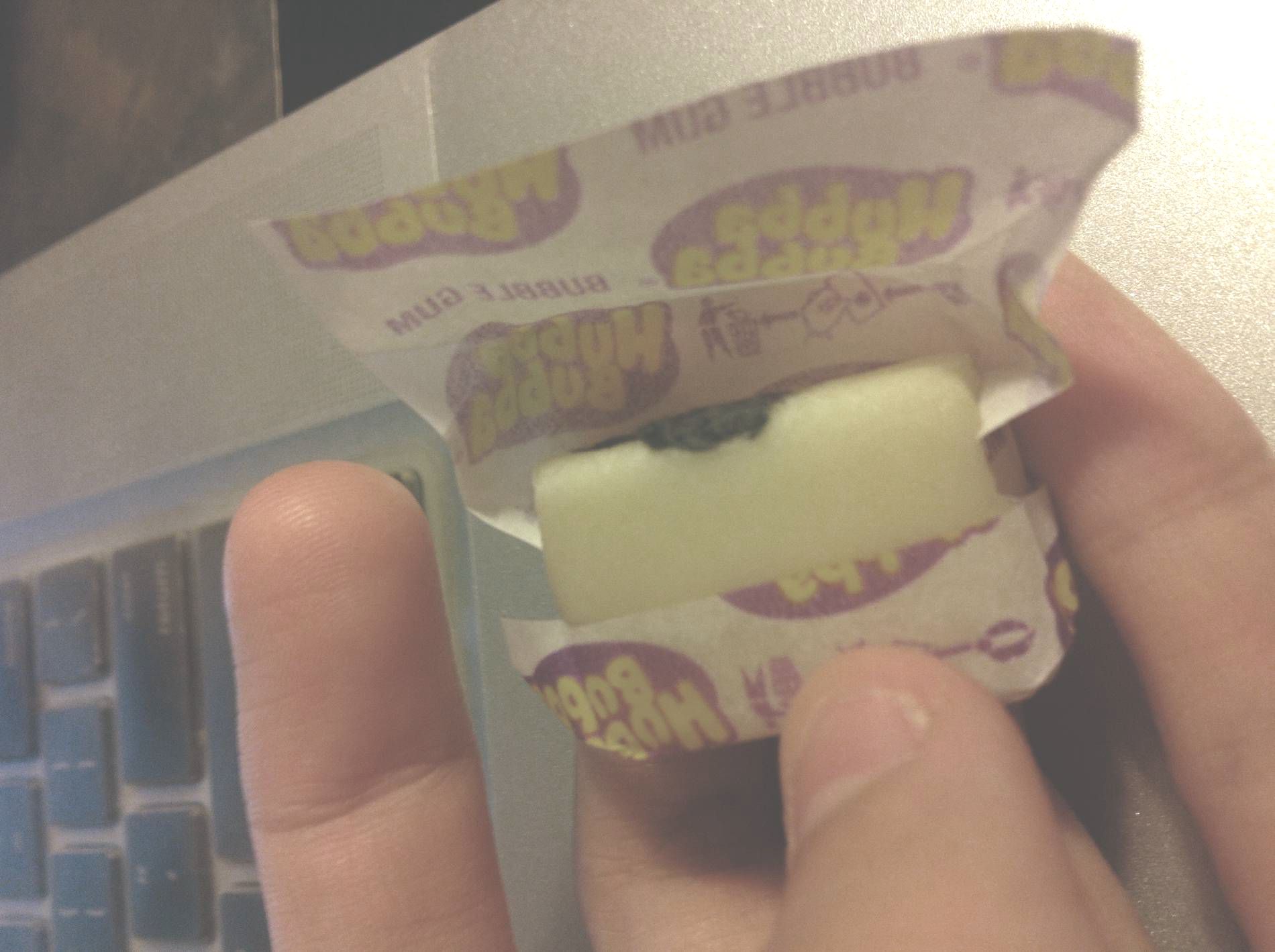

“From Dust, To Dust” is a work consisting of four balls of dust and pocket lint, collected and traded between Singapore and London. Over an 8-month period when we were unavoidably living in different countries, we played a game in which we collected and traded our pocket lint between Singapore and London – smuggling it in the corners and crevices of small objects, and mailing these objects to each other. The balls of lint on display are composed of our traded lint.

Year

2013

Medium

Dust balls.

Exhibition History

Bermonsey Project Space.

Page updated: 22 June 2023

THE BIG QUESTION

How do the bits of lint accumulate?

ARTWORK IMAGES

.jpg)

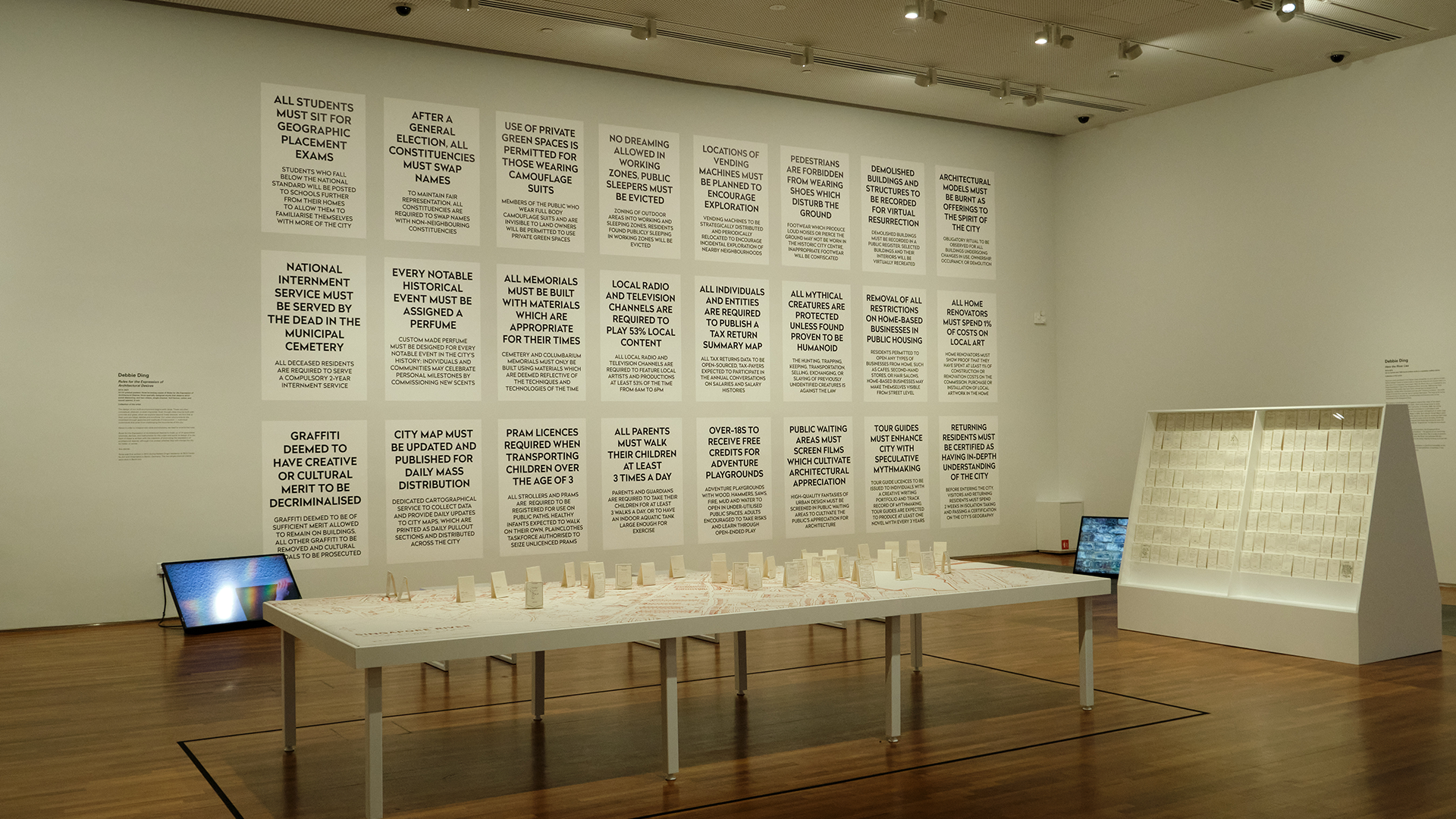

EXHIBITION VIEW

PROCESS / BEHIND THE SCENES