People who have been following this blog or my work for some time might know that I have been getting interested in collecting rocks. Rocks! Stones! Geology! Archaeology! Subjects that are not discussed quite enough in Singapore! But ah, now we are in Paris, where everything is built with stone and rocks! So have you ever wondered, where exactly do the stones in all of Paris’ iconic buildings come from? No? Well, I’m going to tell you more about rocks anyway.

I thought we’d start, for example, with the most famous of famous churches, which would be Saint-Denis, where all of the monarchs of France and their families have been buried from the 10th century until 1789 (with the exception of 3 kings). It stands to reason that such a significant building would have the oldest, the most EPIC and monumental stones. And what else has the ability to say “EPIC” besides a stone that’s more than a thousand years old?

This led to me a book entitled “Working with Limestone: The Science, Technology and Art of Medieval Limestone Monuments” by Vibeke Olson, one of the few English language books on large-scale medieval artistic production and stone studies.

Page 76:

“The French plain, which extends to the north of Paris, is made up of marl, clay and sand, on which the basilica of Saint-Denis and the medieval city that surrounds it were constructed. The Seine flows into an alluvial plain 1,200 m to the west of the basilica. To the north, the Pinson and Montmorency hills edge the horizon. Like the Montmatre and Belleville hills to the south of Saint-Denis, they are formed of gypsum, marls, clays, and Fontainebleau sand/sandstone layers, with the Montmorency cavernous siliceous limestone outcrops at the summits. Upstream, in the valley of Croult, from Garges-les-Gonesse 5km to the northeast of the basilica, the Saint-Ouen lacustrine limestone and the Beauchamp sand/sandstone can be found close to the surface.

Consequently, the material abundance near the city was an important source of local quarry stone and allowed the production of mortar, tiles and plaster. Only the building stones were not available locally and had to be imported. Fortunately the Paris basin is composed regionally of an excellent building stone known as Lutetian limestone (called Calcaire grossier)…”

It is this Calcaire grossier or soft limestone which many parts of the city of Paris was built with. The rest of chapter 5 elaborates more about the quarries and the Lutetian limestone known as the “Paris stone” (pierre de paris) that is found in all the medieval monuments.

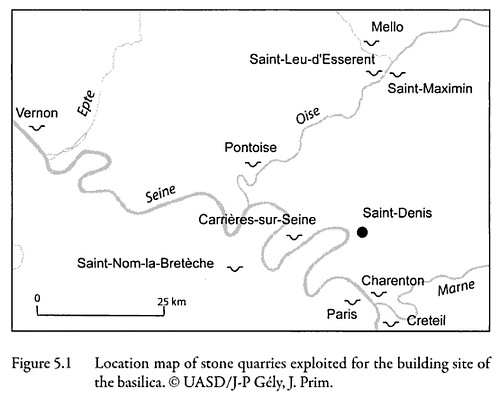

Lutetian limestone was extracted from a few parts of the banks of the Seine during the medieval period, and also in large quarry centers along the Oise river. The stone that was mined there was also called “Oise Stone (pierre de l’Oise) which was used in the nineteenth century and is still actively mining and exporting this stone to other countries and for the restoration of historical monuments. Limestone from these areas can sometimes be very hard or quite soft. Interestingly, in buildings like the basilica of Saint-Denis, they arranged it so that the hard stones faced outwards and the softer stones faced the interior. [One more stone of note is a kind of white hard chalk known as Vernon Stone (pierre de Vernon), mined from a spot approximately 110km from Saint-Denis, which was actually used for the foundations of the building. This Vernon Stone is also used in Normandy building sites. I add this additional fact in just for completeness.]

A slight digression of note at this point would have to do with another area also full of limestone – Cornwall and Lyme Regis. I have a certain interest in the coastline of Lyme Regis due to it being the setting of one of my favorite novels – John Fowles’ “The French Lieutenant’s Woman”. Now, although later searching reveals that the origins of the name “Lyme Regis” comes from its proximity to a River Lym as first named by the Romans, I must admit that for some time I had thought the “Lyme” in “Lyme Regis” was related to the abundance of limestone (lime being calcium oxide) and all of its ancient fossils in the region. Many famous dinosaur fossils were found on the coasts of Lyme Regis (some by the famous palaeontologist Mary Anning), and limestone itself is a kind of rock that is likely to have been made from the skeletal remains of all the little marine organisms that teem in the seas. It is famously noted that Jane Austen had visited it three times and wrote it into her final novel, Persuasion. I am not so much an Austen fan to have noted this, but I learnt of the fictional fall of her character of Louisa Musgrove from Fowles’ book, where the fictional victorian character of Ernestina notes, while fictionally walking down a flight of stairs that exists in reality, that “these are the very steps that Jane Austen made Louisa Musgrove fall down in Persuasion‘. Oh! What a dramatic accident! Apparently even Lord Tennyson was said to have commented (when he arrived in Lyme Regis):

“Don’t talk to me of the Duke of Monmouth. Show me the exact spot where Louisa Musgrove fell!”

Speaking of accidents, if one goes about searching for tours to either the quarries or the coast, one will see information stating that some areas and sites are considered unsafe for long visits because of the possibility of “geological accidents”. This is a little vague sometimes. This particular phasing of words attracted me, because on one hand I knew it was used to describe true accidents in the sense of the word, like if parts of the rocks dislodged themselves and hit someone, that would be a geological accident. Or, if someone fell off whilst in the midst of a geological study, perhaps it would be called a geological accident. But then again, in its most obvious form, the term could also refer to geological anomalies such as fissures or faults. Last of all, geological accidents could also refer to the accidents by little animals and creatures that were compressed into the rocks to form fossils. So it is a pretty flexible term. Perhaps all of the above scenarios illustrate the dangers of being near rocks:

Geological Accidents:

(1) being hit by falling rocks

(2) falling off rocks

(3) earthquakes and other actual geological events

(4) becoming compacted and eventually fossilised, by accident

These are just meandering collections of facts at this point, so let’s go back to the city of Paris. I found in another article (in french) that notes that since a lot of Paris was built from materials from Paris itself, the mining of gypsum and limestone in the city also gave rise to huge underground caverns and “catacombs”. “Les Catacombes de Paris”! The article also seems to be describing how the catacombs are built in the process of mining for limestone. I wonder if I can visit them?

I’ve also found another link to a “Stone heritage centre in Saint Maximin, which is said to have been the source for stones that were “used to build Les Invalides, the Palais Bourbon and the Place de la Concorde”! Their simple website also writes: “The Maison de la Pierre (“stone-heritage centre”) of southern Oise seeks to develop “stone tourism”: cultural and industrial tourism centred around the department’s important stone heritage…”

French people! I’ve never heard of “STONE TOURISM” before – is this phrase the result of some wonky french-to-english translations? Or are they attempting to come up with a new, cutting-edge tagline here? Either way, I don’t mind going out to visit Oise as a Stone Tourist, as long as I get to witness some geological accidents along the way. Yeah baby.

See also:

Where Exactly did Louisa Musgrove Fall?

Les Anciennes Carrieres Du Calcaire Grossier a Paris

Comité Français d’Histoire de la Géologie