Russian Coulibiac – still a mystery on the inside (Image Source: wikimedia commons)

Recently I was reading an article in the New Yorker – “Notes of a Gastronome: Cooking with Daniel” by Bill Buford, in which he describes his painstaking attempts to recreate various ‘lost’ recipes, such as the dish known as the “coulibiac”. By all accounts, the coulibiac sounds like a very complicated thing to put together well – consisting of a fish pie that has been meticulously assembled with layers of rice, hardboiled eggs, mushroom, and a pastry shell “which prevents you from knowing what is going on underneath”, but which still requires that all must be timed perfectly in order to “catch fish and pastry crossing a finishing line in different degrees of doneness at the same time”. It was brought to France and rose to its fame in the culinary world when it was selected for inclusion in the masterpiece “The Complete Guide to the Art of Modern Cookery”, penned by the famed French Chef Auguste Escoffier, where was popular in the 1870s.

The article describes various attempts to recreate the dish from a state in which its description is nothing other than vague and for the highly trained chefs trying to make it from its original description in Escoffier’s book, even they begin to suspect that something must be wrong with the dish’s architecture, because of the seeming difficulty of getting both pastry and fish to agree to work together at the same time. A hilarious passage in the article describes the master chefs becoming increasingly more frustrated with each successive failure, and how the hapless coulibiac is “touched, poked, turn this way, turned back, bumped, and in every possible manner fussed with…”

From the article: “I found, in all this, a resoundingly obvious lesson: if cooking knowledge is not carefully passed from one generation to the next, it doesn’t last. For instance, if you look up coulibiac in the 1938 edition of Larousse Gastronomique, you will find plenty, including an intitial account of the dish’s origins, a warm pastry with fish inside, an acknowledgment of its Russianness, and a grainy photograph of a loaf-like entity, twelve steam slits on top, sitting bluntly on a platter, emanating rustic veracity. From the entry, you may not be able to replicate the dish, but you’ll understand what it is. In the recent Larousse Gastronomique, published sixty-nine years later and edited by Joel Robuchon, a high prince of nouvelle cuisine, the passage has been rewritten. It has no picture, makes no mention of the vesiga, doesn’t specify the pastry, and describes the dish in terms that suggest a sack that can be filled with meat, vegetables, fish, yesterday’s newspapers, whatever (…) I felt like a witness to a disappearing food history. When a dish falls out of the repertoire, the know-how goes with it. In less than seventy years, it was going, it was almost gone: pfiff…”

The rest of the account of the Coulibiac is about how they trace the origins of this lost recipe; its russian roots and the French coulibiac it inspired which might take some cues from the Russian original but yet would not be obliged to follow the recipe to a tee. It appears the Coulibiac’s success was all down to an obscure ingredient, the vesiga or “vyaziga” – the dried spinal marrow of a sturgeon fish in particular which will practically melt in the mouth when cooked properly, and the use of kasha buckwheat of slavic origins rather than rice. And if you look up vesiga on the internet or coulibiac you will only find too much information on an ingredient you can’t find anyway.

The shifting sands of food history! I suppose food history is something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately ever since I got more and more excited about cooking (or about food science). I like to think I am interested in wild culinary experimentations, but simultaneously also interested in understanding traditional origins of food and making it the basis from which I experiment or deviate from – or improve on, with the power of SCIENCE! and… a trusty kitchen timer and food thermometer…

Nids d’oeufs / Egg nests

Which brings me to the story of the egg nest. One of the ingredients I have been obsessed about cooking for the last few years would be eggs. Over time, I have developed my own methods for the perfect omelette (high heat, sufficient oil, press gently with spatula in centre so the browning is perfect and even), the perfect sunny side up (break into well-oiled pan at very high heat, place pot lid over immediately, allow steam to cook the top while the bottom is perfectly browned and crisped), the perfect hardboiled egg (place egg in pot of room temperature water, bring to a boil and count four minutes from that point, then remove immediately and run under ice water so that the yolk will remain soft and slightly runny but the white will be firm but very delicately cooked). Had I the money to invest in a waterbath and a sous vide setup I would, because I would be really interested in experimenting with the temperature at which the various components of the egg cooks. And beyond the sous vide, I am a fan of the maillard reaction and the flavour it imparts to foods – and the necessity to brown certain foods in order to bring out a specific flavour. You could say that I’ve obsessed over the methods in which one can cook a simple egg for many years.

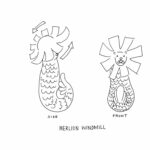

So it comes to my surprise that eventually after all this time I have finally encountered a recipe for an “Egg Nest”. The website describes that the recipe comes from a children’s cookbook “La cuisine est un jeu d’enfants” by Michel Oliver, in which egg whites and egg yolks are seperated and the egg whites are beaten into soft peaks, after which grated gruyere cheese and a pinch of salt for each egg is introduced into the whites and folded in.

The fluffy nests of egg whites are arranged on a baking tray and baked for 3 minutes on their own at 230ªC, after which the yolks are introduced back into the centre of the nests and baked for another 3 minutes. After which you can invite it to the party in your mouth…

The result is an airy, puffy egg with the mildness of the gruyere with gorgeously browned peaks as the proteins in egg whites and the gruyere cheese are wont to do. How can it be that there is no other common term for this method of cooking eggs? I can understand how Chinese-style steamed eggs may not be as popular in the western world, but the egg nest itself seems so fiendishly simple and logical to prepare in a western kitchen, so why hasn’t it become more popular? Why don’t we have a special name for it, like how we do have a name for devilled eggs?

In any case, I think the discovery of the recipe of the Egg Nest fills me with hope that since even the well-explored territory of egg cooking has clearly not reached its limits, surely there must be so many more methods and recipes to be discovered, either through experimentation or the rediscovery of lost recipes….

In the interest of people who may find my food shenanigans out of line with the general theme of this blog, here’s a summarised description of my recent notable bakes/cooks (so you will only have to see it once and all in one post):

Japanese CheesecakeI made this for George’s birthday the other day – the main weighing scale was broken so I guesstimated everything using a tablespoon. Surprisingly it did not fall apart. Usually how these things come about is that I read a few recipes from books or online and then make up something logical from the lot of them and what I understand from the purpose of each ingredient. The amounts I had been aiming for were: 5 egg whites – to be whisked into soft peaks Combine all without flattening the mixture too much and pour into cake pan lined with many layers of tinfoil on the outside. Find an EVEN BIGGER baking tray and half-submerge your cake pan in a waterbath of boiling water and bake this entire precariously watery cake bath setup in the oven at 160ªC for 1 hour, then reduce to 150ªC and bake for another half hour, then finally take out of the water bath and let it rest for at least fifteen minutes before serving. It may be better served chilled depending on your preferences. |

Potemkin Apple PieWhat is an apple pie? Surely the basics of it must be sugar, and apple, and pastry. And besides the pastry, sugar and apples are common things to be found in the average kitchen. So why couldn’t we make an apple pie on the spur of the moment, if we had the pastry also sorted? I noticed recently that there were pre-made pastry rolls available at the Sainsbury’s, since our flatmate Salsa has been making lots of tasty Boreks with filo pastry. I bought a roll of shortbread pastry the other day for food emergencies and sure enough there came a day when the George desired a sweet dessert, and I was sure that I could invent an apple pie out of whatever we had in the house. You just need: In a small pastry dish, assemble a pastry sculpture which resembles the stereotypical image of a lattice top apple pie. Inside this pie, liberally smear the sugar all over the apple slices and the raisins. With some luck it will look a bit like an apple pie and actually taste similar to a primitive apple pie. With some luck you’ll have everyone fooled that you know what is an apple pie in no time. |

Banana CupcakeThis was the maddest banana cupcake ever. There were two very sad and very soft bananas languishing in the food cabinet. So i decided to bake them into a cupcake. It is unreal that two sad and old bananas make twelve very awesome banana cupcakes. Are cupcakes really so simple? 125 g caster sugar Mix everything together, pour into cupcake trays and bake at 180ªC for about 20-25 min or until golden on top. |

Chinese Braised Tau Pok (Tofu Puff)This was more of a hit than I expected. I wanted to illustrate to George how people often cook tau pok in Singapore – sliced into triangles and simmered until soft in a soy-based sauce, and this vegetarian adaptation turned out excellently well as I recall it. Onions, carrots, potatoes, spring onions Cut tofu puffs into triangles. Fry all the vegetables until soft and then pour the sauces over and leave to simmer slowly for at least 20 minutes or however long you can humanly stand. Finally, when almost ready to serve, add the cornflour and water to thicken it into a sauce. Stir and cook for about 5-10 minutes more until sauce thickens. |

Mie Goreng Jawa (Indonesian Fried Noodle)I used to be crazy about Mee Goreng. Sadly I’m not in a place where I can go around the cornershop to get one made for me, but the recent discovery of kecap manis has enabled me to recreate a pretty decent (vegetarian) version of Mie Goreng Jawa. I think this works. (I also find that Oyster mushrooms can be useful for adding some depth of flavour in asian dishes which typically call for meat/seafood, especially when making a vegetarian version…) 400 g yellow egg noodles Cook the onion until almost caramelized, stirfry the mushrooms and vegetables separately first until they are already cooked to the point where you want them to be later, and scramble the egg in advance separately. Remove them from the fire temporarily and pan fry the egg noodles with the onions and then add all the other ingredients back into the pan. Finally, add the sauces, mix well and stir fry for a few more minutes and that’s it. |

Vegetable LasagnaI don’t even really have a recipe for this. Basically, I think of this as a kind of rich tomato stew that is placed inbetween layers of lasagna, mozzarella cheese, and bechamel sauce. Go and make any sort of inventive random vegetable stew that has a tomato in it. Use some premade italian tomato passata for the vegetable stew if you will, but for the rest, you must not stint on the bechamel sauce or the cheese! YOU MUST NOT STINT ON THE SAUCE. Basic Bechamel Sauce: The only problem with this recipe is that it will take about 2-3 hours for the average human being to prepare, even though the steps are fiendishly simple. The results however, are delicious and worth repeating… |