Pigeons on Pompidou

Centre Georges Pompidou houses one of the most important contemporary art collections to see in Paris; the collection of the Musée national d’art moderne – with their permanent exhibition of contemporary art from the turn of the century (1905) to 1960, including different movements such as Fauves, Abstract, Cubism, Constructivism, Surrealism, Dada, Bauhaus, Realism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, Nouveau Realisme, Figuration narrative, Arte Povera, Process art, installations, etc.

The Musée national d’art moderne (MNAM, also sometimes known as “National Museum of Modern Art” in English) was only set up in 1947; its initial budgets were modest and most of its early acquisitions were result of donations or bequests. But, starting from 1970s there were more ambitious purchasing policies as there was a concern that “France should retain essential aspects of its national heritage”.

Efforts were apparently made by the different directors to develop the collection in different aspects; Pontus Hulten (Director from 1974-1981) sought to acquire more American art which had hitherto not been exhibited much in France, and also Surrealism and other international art; Dominique Bozo (Director from 1981-1986) also sought to consolidate the Miró, Matisse, Giacometti, Dubuffet, and Léger collections.

From 1968 the French government also put in place an arrangement for heirs of artists and collectors to donate works of art in lieu of inheritance tax, which resulted in a large part of the estates of artists (such as the more than 250 works by Andre Breton which once hung on the wall of his studio on rue Fontaine; masterpieces by Bonnard, Braque, Derain, Dubuffet, Duchamp, Giacometti, Klee, Laurens, Man Ray, Matisse, and Miró; a major part of the estates of artists such as Chagall, Magnelli, Vieira da Silva, and also Derain, Giacometti, and Dubuffet.

Even prior to such tax waiver arrangements by the French government, the collections of the MNAM were also being greatly enhanced by numerous donors (foundations and the artist’s families) who voluntarily donated works to the museum; some of which, for example, such as the donation by Louise and Michel Leiris, added almost two hundred works to the museum (which helped enhance its Cubist art collection tremendously).

This commentary is in three parts:

Accrochage de la collection permanente (de 1905 à 1960)

Collections contemporaines (des années 1960 à nos jours)

La Tendeza – Architectures Italiennes (1965-1983)

A recommended trip would start on the 5th floor with the works from 1905 onwards, allowing one to take a chronological journey through the years, followed by the contemporary exhibition of works from 1960s till today (with quite a few masterpieces and iconic pieces).

6th floor – Other Exhibitions & Restaurant

5th floor – 1905 to 1960

4th floor – 1960 to present & Other Exhibitions

The only problem is that the 5th floor is not directly accessible and one must enter at the 4th floor and go up to the 5th. Lifts do not access the 5th floor directly from the 1st floor, and the lift to those levels only serve the 4th and 5th floors. This means when one first enters the 4th floor, one should take the escalator straight ahead and start one’s walk from the 5th floor first.

Not sure what manner of french logic caused them to design it this way, since due to confusing signage and unexpected closures of certain passageways and entrances/exits, we ended up seeing the contemporaries show before the earlier modern works and generally walking in circles and and taking various escalators and lifts up and down and up and down and all around…

[SOME TIME LATER: The author of this post discovers that this illogical ordering of objects and complete breakdown in logic and directions is a trend that will continue to persist when exploring other locations in Paris. Also, they do not care much for cleanliness, as we found a mouse in the Louvre’s restaurant and when I politely informed a waiter, he shrugged and said, “Ah! That is life…”]

Musée national d’art moderne, Accrochage de la collection permanente (de 1905 à 1960) [niveau 5]

Fauvism: The exhibition begins with Fauvism, which was emphasized the use of pure color and orderly surfaces, which was a revolution in pushing for experimentation, and the autonomy of form and color from fine art itself. The term originates from a comment by critic Louis Vauxcelles’ comparing these works to the old masters as “Donatello among the wild beats (fauves)”.

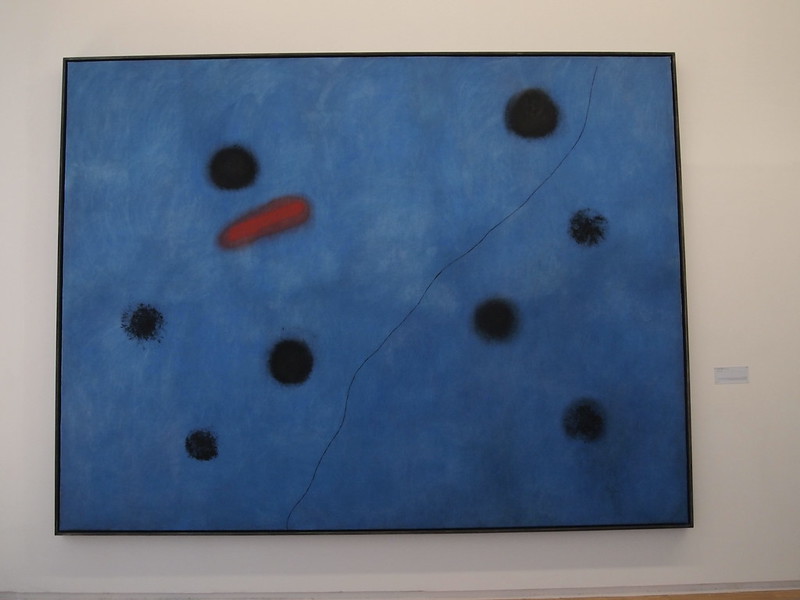

Joan Miró – La Sieste (The Siesta, 1925)

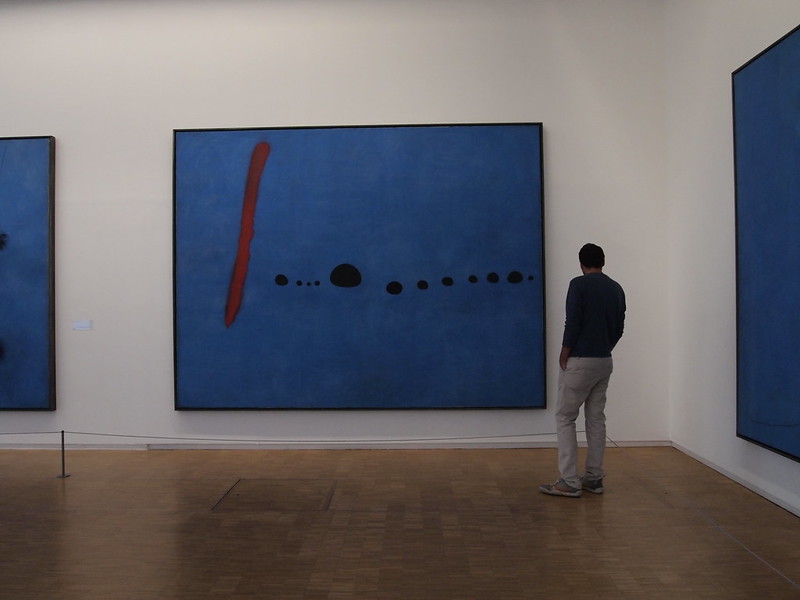

Many of Miró’s trademark blue canvases here, said to be the “color of his dreams”. “‘Perfecting’ the background put me in the right state to continue”; he said this of the long process of thinking and preparing himself to paint them.

Joan Miró – Bleus

Albert Marquet – La plage de fécamp (1906)

After Fauvism: After 1907, Fauvism toned down; with influences from more primitive art which had inspired more simplification of form. The geometric harmonies and rhythm of pieces became more important; so there were fewer colors, but of pure intense tones (with very little diffusion of colors), and the line was also used to dynamic effects.

Alberto Magnelli – Les ouvriers sur la charrette (1914)

One can see the “cubist” construction styles in this after Magnelli met with Léger, Matisse, and Picasso in Paris in 1914.

Juan Gris – Nature morte sur une chaise (Still Life on a Chair, 1917)

Gris became a cubist in 1911 after being strongly influenced by Picasso and Braque. From wall text: “The painting reveals the tension between reference to reality [in the chair, the pitcher, the parquet, etc] and its abstract architecture, flat and colour-based, which here takes precedence over the embodiment of a subject” – I should add that the audio commentary also mentions one of the cubists saying it is very hard to draw the space between the apple and the table, because it still is part of the space in a still life, so actually the hardest part to draw is in fact the space around the things.

Henri Laurens – La bouteille de Beaune (The Beaune Bottle, 1918)

Beaune refers to the address of Laurens’s dealer Leonce Rosenberg, whose gallery was situated at the Rue de Beaune in Paris.

Cubism: Brasque and Picasso created Cubism and its main years were between 1907 and 1914. This of course is significant because it was the movement that gave rise to the idea of art as an intellectual construction rather than naturalistic or realistic expressions. Flattening and deconstruction of spaces, perspectives, objects, and distortions of color and narrative with fragments and half-outlines of shapes.

Pablo Picasso – Filette au cerceau (1919)

Pablo Picasso – Le violon (1914)

Pablo Picasso – Le Guitariste (1910)

Georges Braque – Nature morte au violon (1911)

Georges Braque – Femme a la guitare (1913)

Detail from Georges Braque – Femme a la guitare (1913)

Abstract Expressionism: This line of research continued into something that is now described as Abstraction or Abstract Expressionism, such as exploring forms which did not exist in reality; ie: the ability to create non-figurative art. It was sometimes inspired by music. Kandinsky wrote in a letter to Schönberg (Austrian composer of atonal music) that he would “show, however, that construction is also to be attained by the principle of dissonance (…) I think I can find something between sight and hearing and I can produce a fugue in colours as Bach has done in music.”

Robert Delaunay – Formes Circulaires, Soleil Nº 2, (1912-1913)

Sonia Delaunay – Prismes électriques (1914)

By the wife of Robert Delaunay.

Union des Artistes Moderne: At this time there was also a break away from the rich and opulent decorative styles that had defined most “decorative arts” in museums. Led by Robert Mallet-Stevens, the Union des Artistes Moderne (UAM) included artists from all areas such as painters, sculptors, architects, furniture designers, fabric designers, goldsmiths, glassmakers, etc – all of which were working towards a kind of modernity, and rejecting the habit of celebrating that which was rich and extravagant and visually “inherited” from the older generation.

Fernand Léger – Composition à la main et aux chapeau (1927)

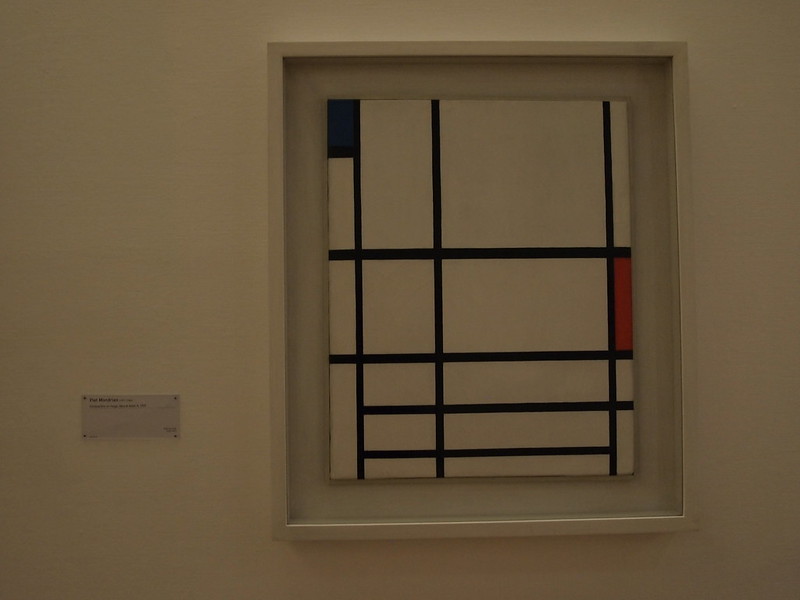

Piet Mondrian – Tableau (1921)

Antoine Pevsner – Masque (1923)

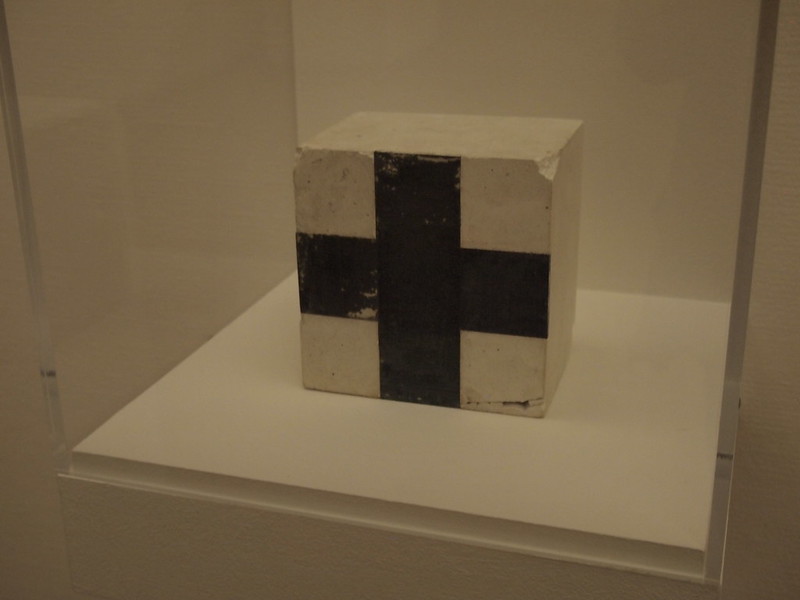

Kasimir Malévitch – Croix [noire] (1915)

On a side note, by this point we were no longer able to tell if the lights above (which we had just noticed for the first time) were part of the works or simply a design feature of the entire museum.

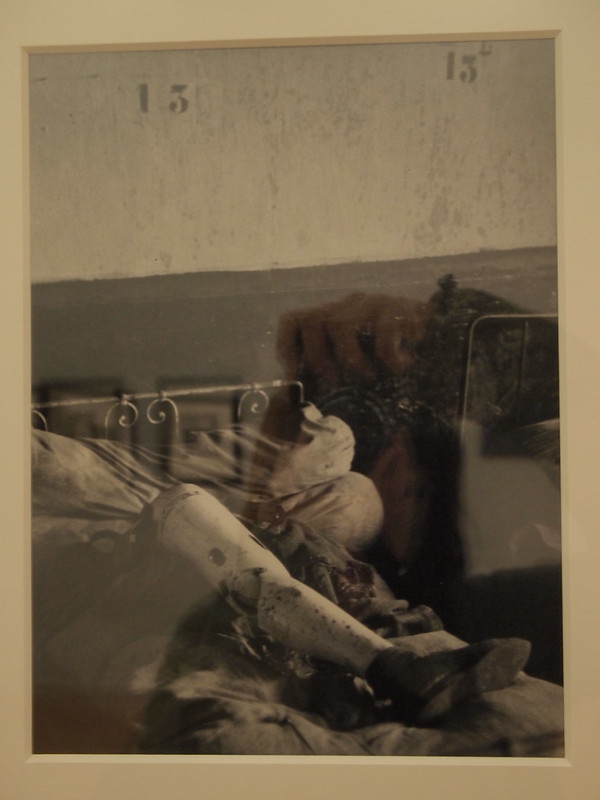

Social Fantastic: This has a small off-tangent that seems more thematic than an actual movement. The literary idea of the “Social Fantastic” is said to have been invented by writer Pierre Mac Orlan, finding poetry in (stock) characters such as “the melancholy pedestrian, the petty rook, the prostitute”, and is set in (now predictably “poetic” or “romanticized” settings such as “the abattoir, the quay-side, the dark alley”. The feeling embodied by works in the period is an awareness that the conditions are ripe for another catastrophe even though the First World War (the great war) had just subsided at that time, but tensions were still present. One needs to seek out the “social fanatastic” because the threatening and erotic tends to be hidden, because “man is in the habit of disposing of undesirable or harmful elements that threaten his existence.”

As a writer and critic, Mac Orlan celebrated the ability of the monochrome black and white photograph’s ability to capture the details which betrayed the secret life of cities – the “social fantastic” that lay behind everyday life amidst the monumental facades of the big city. (On a side note, Orlan was also a writer of pornographic novels, which frequently depicted flagellation and sado-masochism, but under another pseudonym…)

Eli Lotar – Aux abattoir de la Villette (1929)

Andre Kertesz – Hotel de l’Avenir (1929)

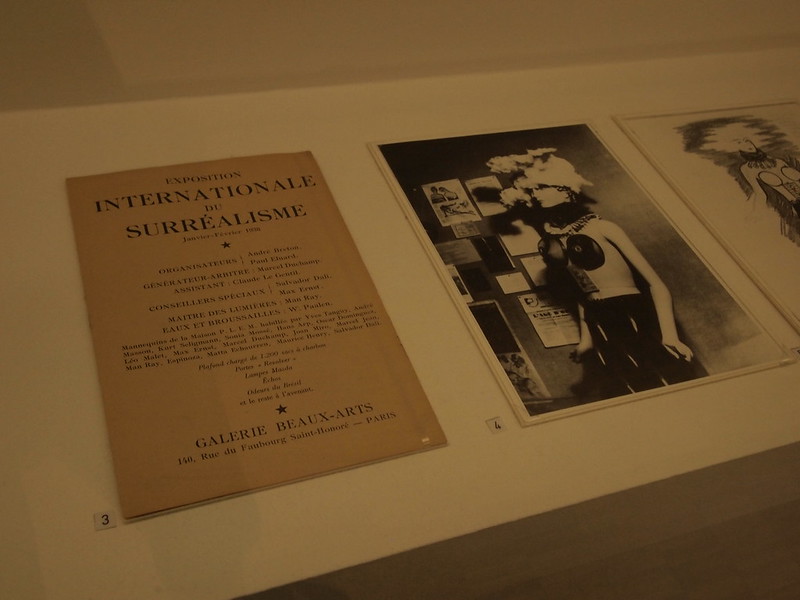

Surrealism: Now, we finally come to Surrealism, as brought together by André Breton in his Surrealist Manifesto of 1924. The term was coined by Apollinaire in 1917 and relied heavily on the idea of producing works and images through “automatism” – like an expression of a life of dreaming; expressions of the unconscious. Some of Giacometti’s sculptures were also built to be “disagreeable objects to be thrown away”, like memories of dreams and expressions of the unconscious that slip away in the waking hours.

Alberto Giacometti – Pointe a l’oeil (1931-1932)

This work was originally called “Relations desagrégeantes” (Disintegrating Relations) but was renamed as “Pointe a l’oeil” (Point to the Eye) in 1947 – like a point threatening the eye in a skull head; wall text notes that Giacometti wrote in 1947, that the menace to the human figure almost without reach of the dagger gaze of a “pineal eye” is the danger of death. The piece can actually be manipulated and elements can swing on their axis but are both on the same base so it is like a russian roulette of attraction and repulsion. (Sadly in this presentation it is behind a glass case and we cannot blow or move it)

Alberto Giacometti – Objet désagréable (1931)

Exposition International du Surréalisme

Max Ernst – Ubu Imperator (1923)

Giorgio De Chirico – Portrait premonitoire de Guillaume Apollinaire (1914)

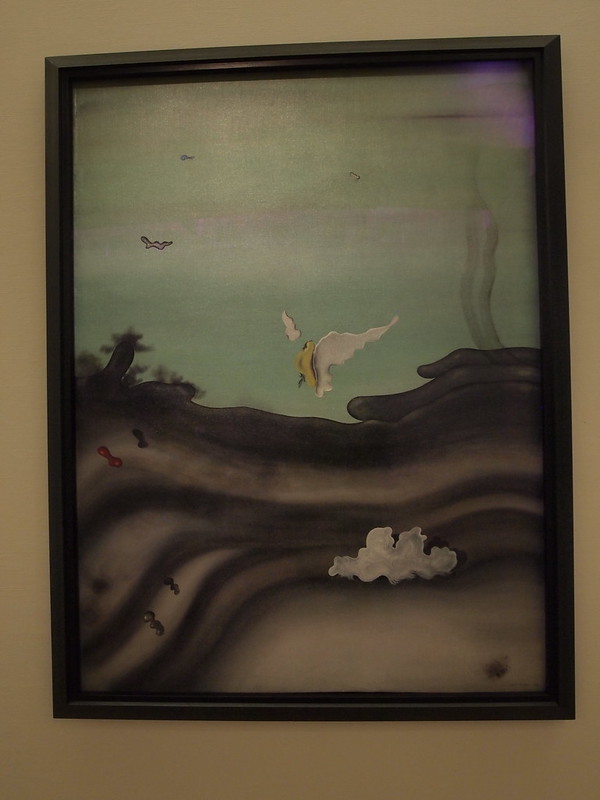

Yves Tanguy – A quatre heures d’été, l’espoir (1929)

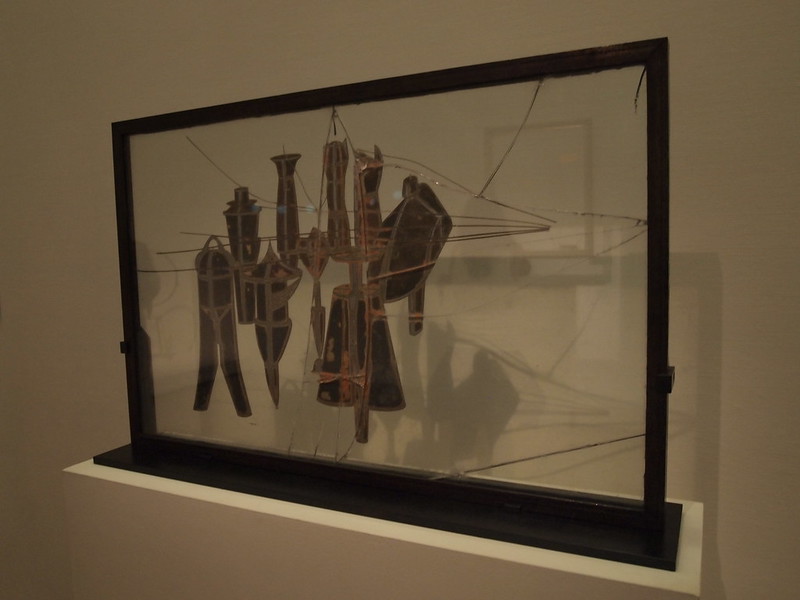

Marcel Duchamp – The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors (The Large Glass) (1915-1923)

Finally we meet the famous large glass in person. I must admit this was not how precisely I imagined it to be. But it is very different to see it in a black and white print on a flat page, as compared this peculiar form in glass and metal and cracks and all.

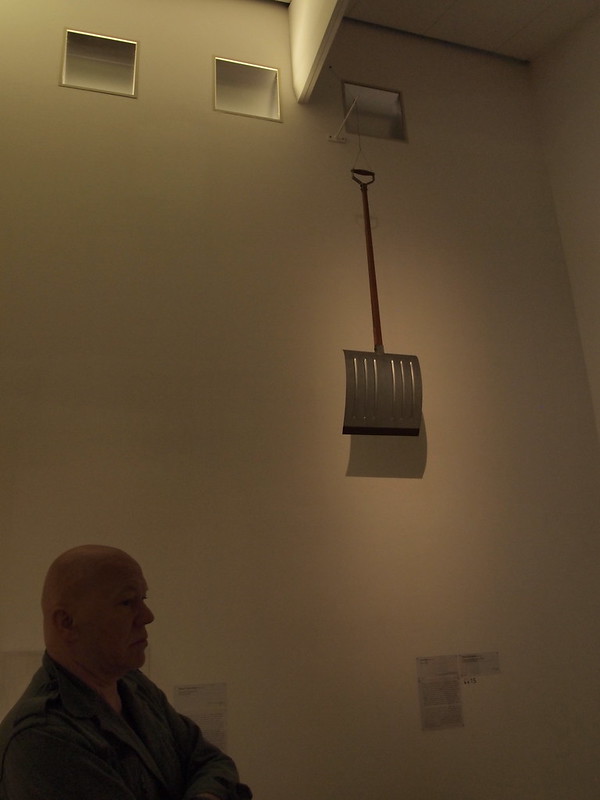

Marcel Duchamp – In advance of the broken arm (1915/1964)

Francis Picabia – Danse de Saint-Guy (1919/1949)

Dada: This was described as the “apogee of Dada subversion” – “a transparent painting without canvas or paint, reduced to the absurdity of a frame with string and labels, to no more than its packaging and description”. It was to be hung from the ceiling and not mounted from a wall, and Picabia also wanted to mount a little wheel behind it, driven by two white mice, and then to send this work to the Salon des artistes indépendants of 1922 to deliver a challenge to the established conventions of art of the time.

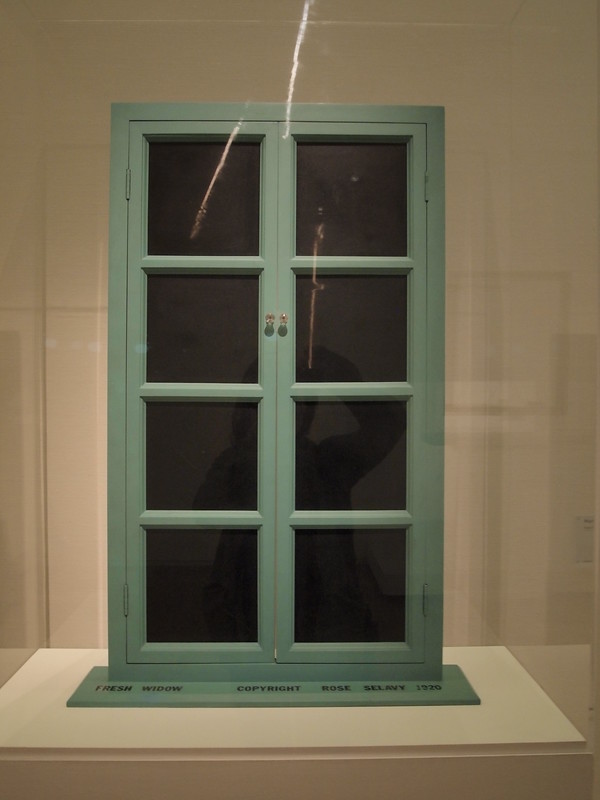

Marcel Duchamp – Fresh Widow (1920/1964)

Basically now from this point, the concept of dada is an anti-art; where anything was permitted as long as it attacked the ideas of art, aesthetics, or morality. Provocation and absurdity. And then of course the ready-mades: to use an ordinary object and raise it to the dignity of a work of art through the artist’s designation of the object as “art”.

Marcel Duchamp – Roue de bicyclette (1913/1964)

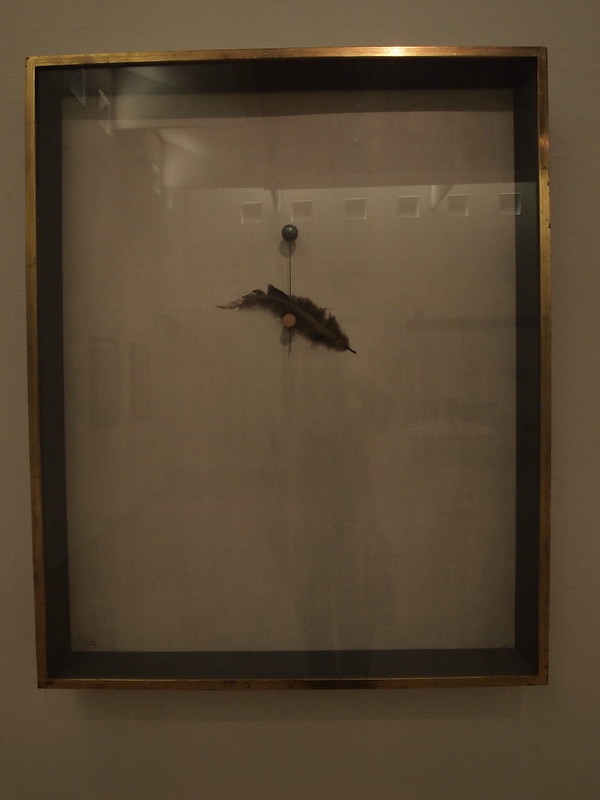

Man Ray – Danger/Dancer (1917-1920)

Joan Miro – Portrait d’une danseuse (1928)

Biomorphism: Biomorphism emerges in the mid-1920s, where curvy, round, and sinuous lines reminiscent of the Art Nouveau aesthetic began to appear – as if they were biological forms from nature. In 1936, Alfred H Barr Jr coined the term biomorphism in order to distinguish it from the geometric abstraction of cubism. This wasn’t a particular movement or anything concerted, but the result of many of the Surrealists using organic forms by chance; probably because they might have drawn some inspiration from biological illustrations.

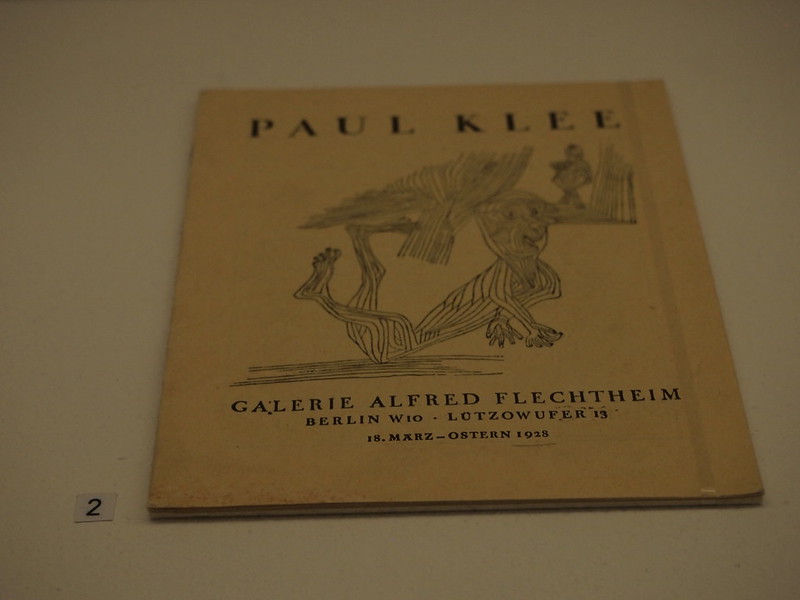

Paul Klee

Sculptures by Jean Arp and Alexander Calder

On the left, some photography of ladies’ bottoms by Raoul Hausmann, and on the right, some photography of blooming flowers. And some animations of what looks like cells multiplying, as if it were under a microscope. Where are all the women artists in all these?

Vassily Kandinsky – Trente (1937)

The controversially famous “Alice” by Balthus. (1933) Controversial because the woman in the picture was recognisable to society (Betty Holland) and because of its perceived “indecency”, despite the confidence shown in the image. If you haven’t had art fatigue by this point, wait till you see the second half of the show coming right up…

Marcel Duchamp – Feuille de vigne femelle (1950-1951)

Casting mould for the work.

Unfortunately, the section for Andre Breton was TEMPORARILY CLOSED at the time of the visit. Therefore we sadly lingered about and instead saw a lot of sculptures by Alberto Giacometti outside the room.

Alberto Giacometti – Buste de Diego (1954)

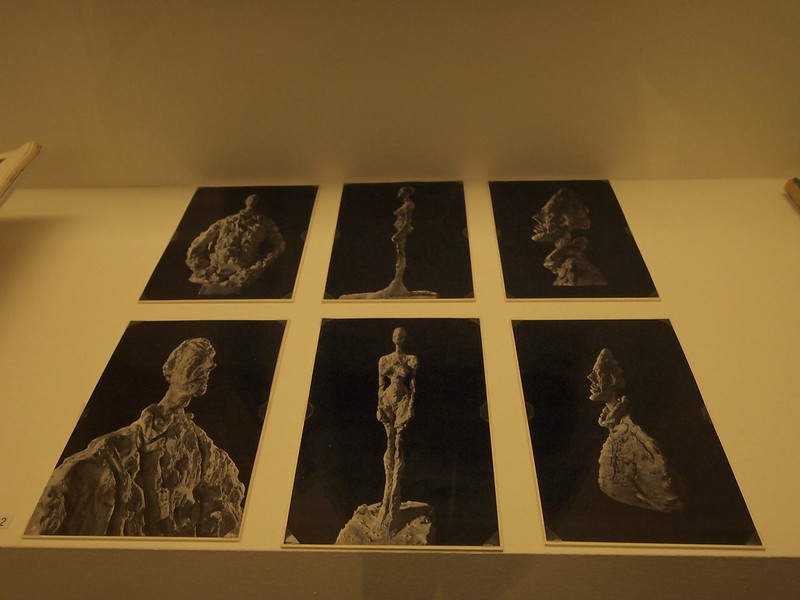

Prints of Alberto Giacometti’s works

At this point, there was a collection of works by Judit Reigl, a hungarian painter who came to Paris in 1950 and whose work looks totally different over the years.

Judit Reigl – Ils ont soif insatiable de l’infini (1950)

Francis Bacon – Three Figures in a room (1964)

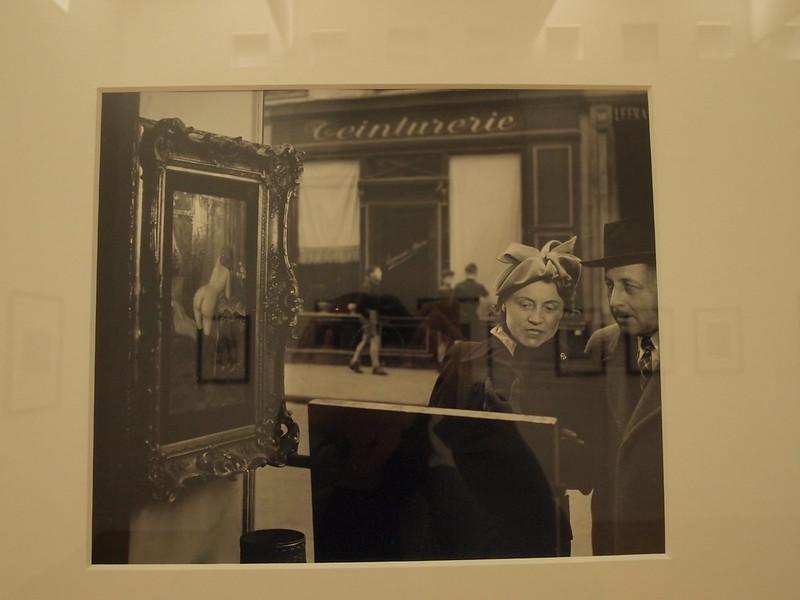

Robert Doisneau – Un regard oblique (1948)

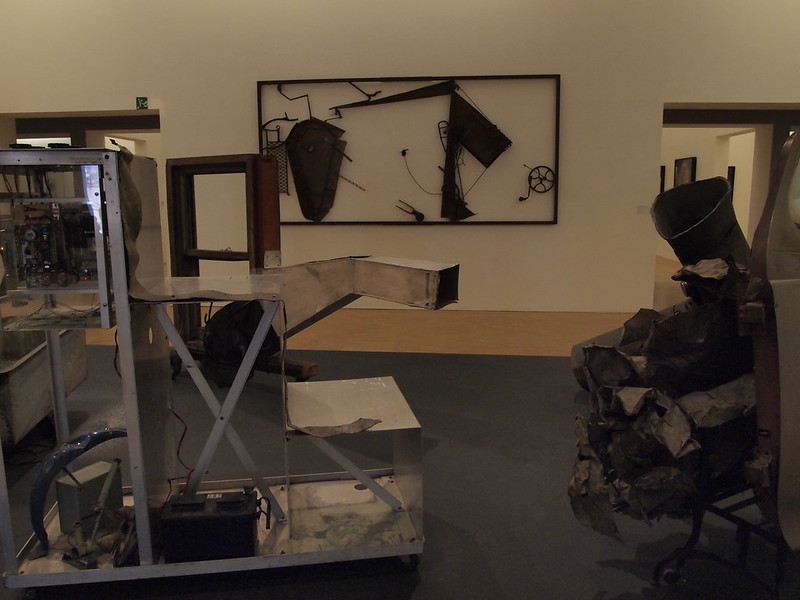

Dada/American Neo-Dada: By now I don’t know what theme it is following, although it is chronological, so the ensuing portion of the gallery appeared to be dedicated to showing their prodigious collection of Dubuffet, and other American Neo-Dada artists/sculptors such as Oldenburg and Rauschenberg who used junk/scrap material to comment on consumer society.

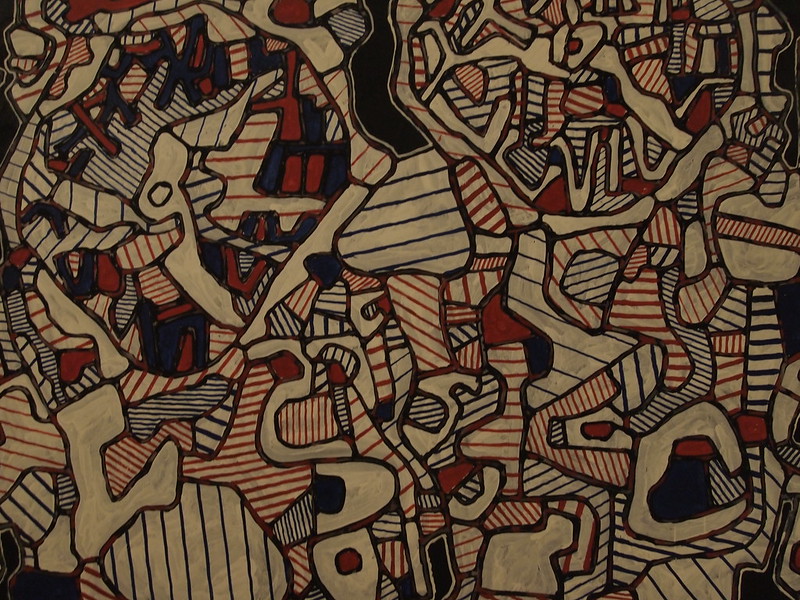

Detail from Jean Dubuffet – La train de pendules (1965)

Jean Dubuffet – Rue Passagere (1961)

Dubuffet’s work followed a form similar to that of art made by children or mentally disabled people who did not conceive of beauty or aesthetics in the same way as adults do.

Robert Rauschenberg – Oracle (1965)

Italian art and design: Suddenly! Italian art and furniture design makes an appearance in the end of this section, with emphasis on the influences from art from Milan in the 1960s. More can be seen of Italian architecture and art in the La Tendeza show, also later on in this post.

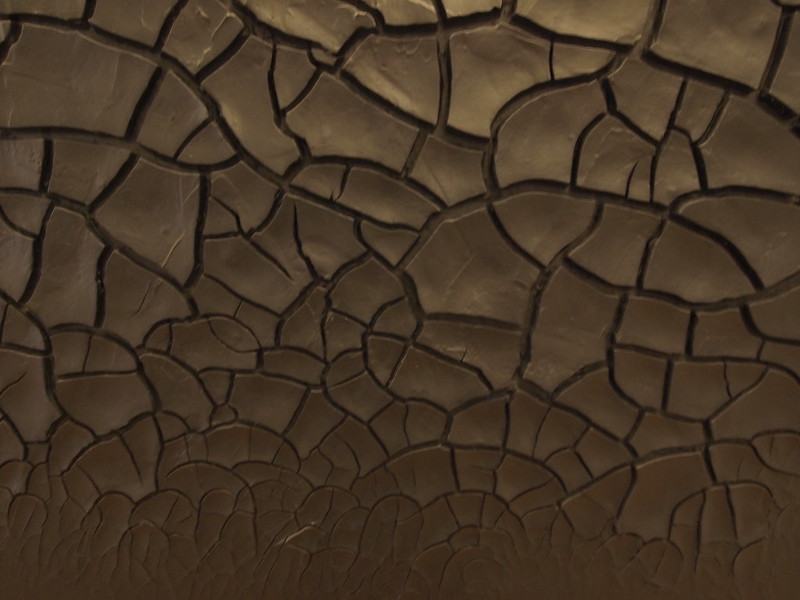

Alberto Burri – Grande cretto nero (1977)

This beautiful work was jet black but in order to capture the cracks my camera has made it appear lighter than it was actually.

Lucio Fontana – Concetto Spaziale

Milan Furniture

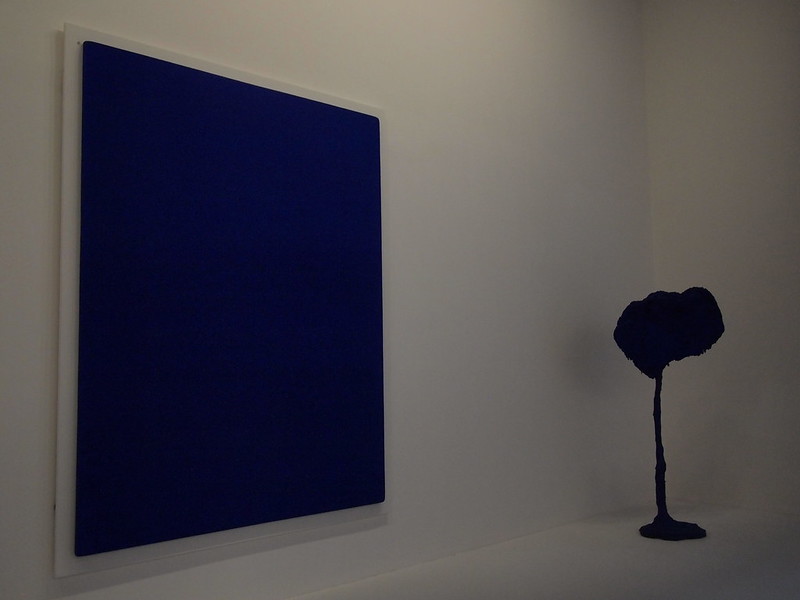

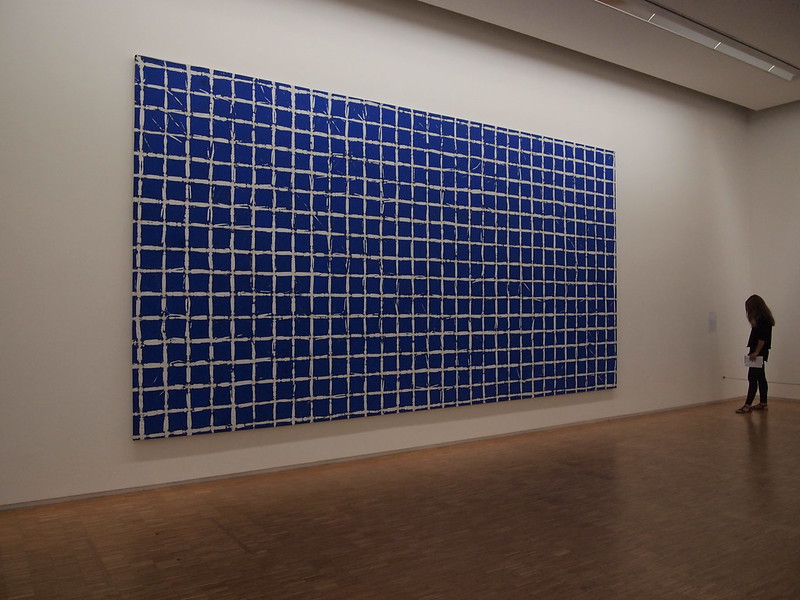

Yves Klein IKB 3, Monochrome bleu sans titre (1960)

Yves Klein invents a new colour of blue and paints everything he makes in this colour, which he calls International Klein Bleu. It is… very strikingly blue and this photo does not do the blue justice. The blue colour becomes the material of the work and he patented the colour in 1960 and he painted everything, including people, with his IKB blue.

As one can tell, we are quickly approaching the modern period. Thank god for that!

Left: Auguste Herbin – Vendredi 1 (1951)

Right: Piet Mondrain – New York City (1962)

Now from there we can go from Piet Mondrain to geometric abstraction. What is that you say? Wasn’t there already geometric abstraction before in Cubism? Why yes, everything goes in cycles. But now, its also moving! And in different materials! And using light or reflection or shadows! And transient! Etc, etc etc…

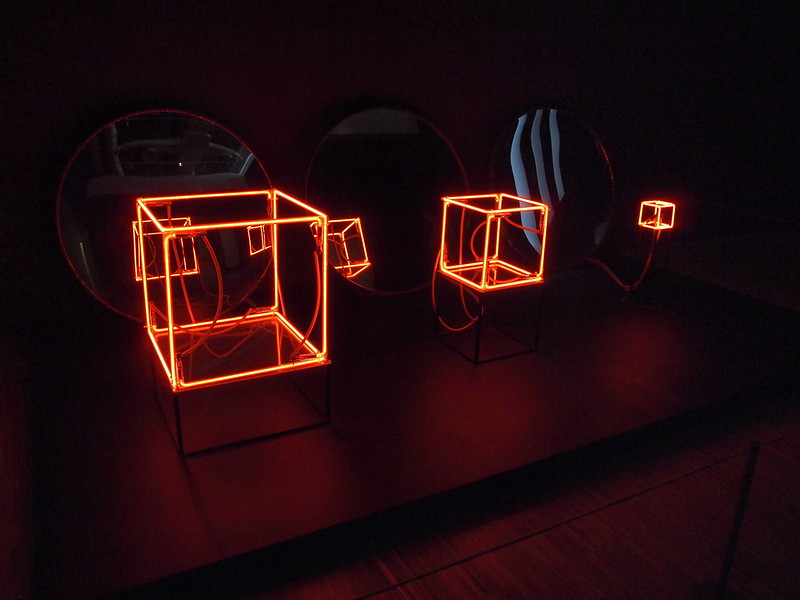

Pietr Kowalski – Identité nº2 (1973)

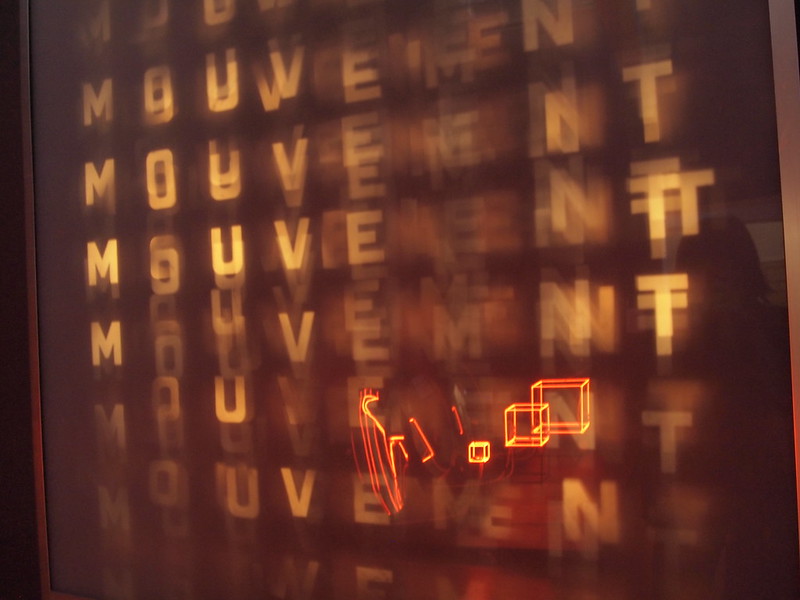

Horacio Garcia-Rossi – Mouvement (1964-1965)

By this point one will certainly have art fatigue after dutifully going through over 60 years of art history in one walk, so here is a picture of Paris to punctuate this art marathon. Because next: we go on to the contemporary collection……..

Collections contemporaines (des années 1960 à nos jours) [niveau 4]

I am unable to write a commentary on this at the moment as the writing of the preceding section has rendered me wordless. I have however, already made a selection of images of works from the contemporary show here….

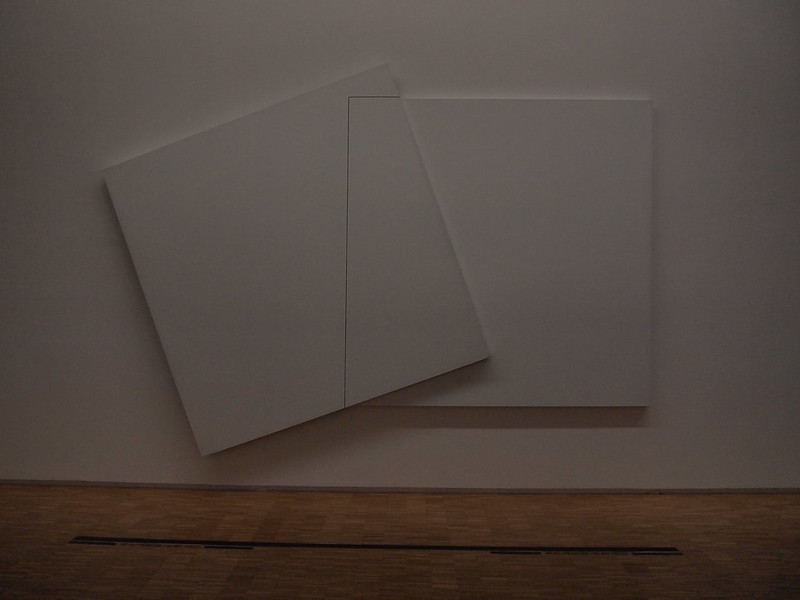

François Morellet – Superposition et transparence

Simon Haitai – Tabula

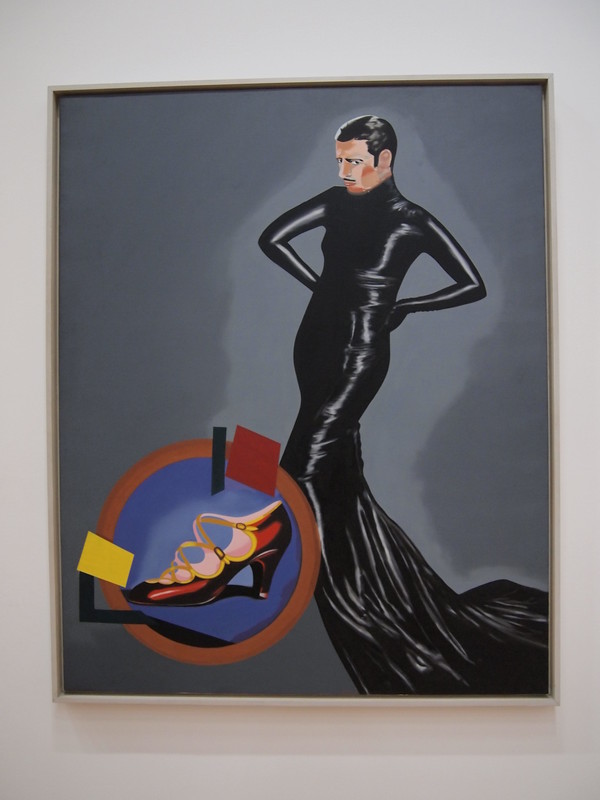

Eduardo Arroyo – El caballero espanol (1970)

Peter Saul – Bewtiful and Stwong (1971)

Erró – Watercolors in Moscow

Philip Guston – In Bed (1971)

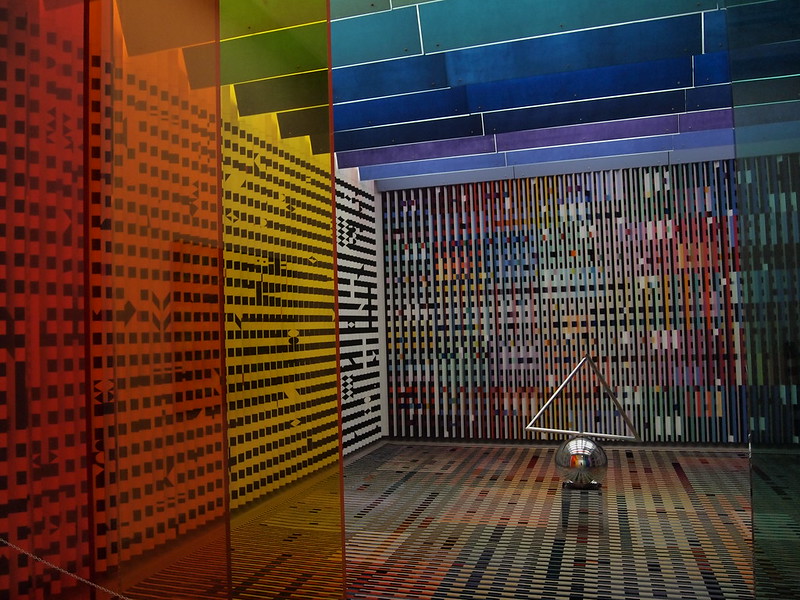

Yaacov Agam – Aménagement de l’antichambre des appartements privés du palais de l’Élysée pour le président Georges Pompidou

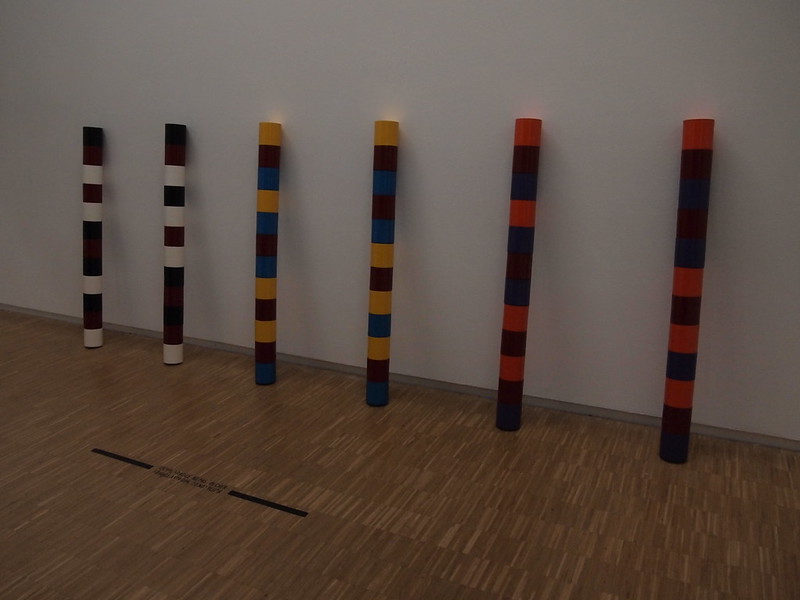

Andre Cadere – Six barres de bois rond (1975)

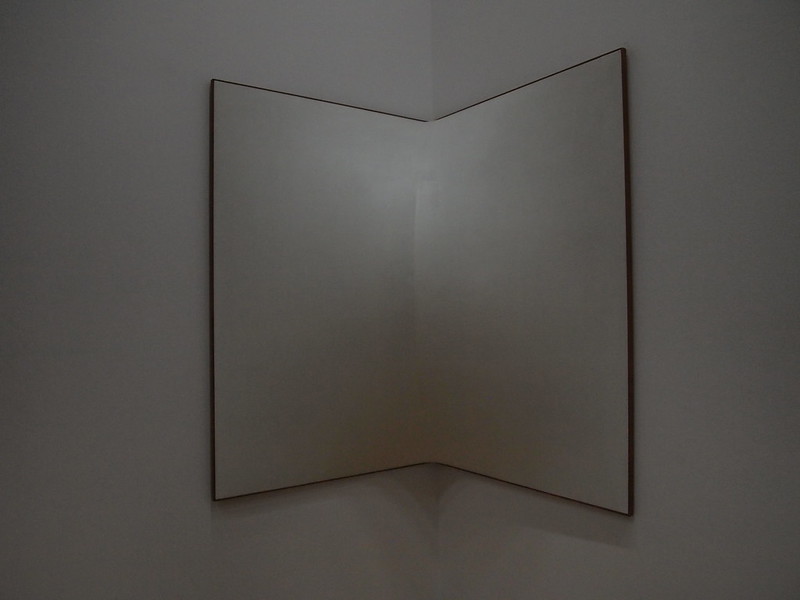

Enrico Castellani – Superficie angolare bianca nº6 (1964)

Joan Mitchell – Chasse Interdite (1973)

Michelangelo Pistoletto – Donna al cimetero (1962/1974)

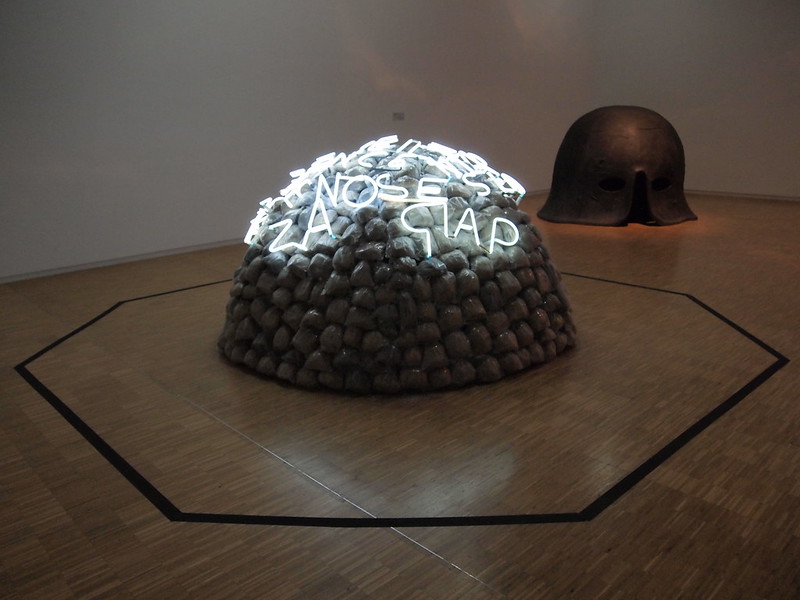

Mario Merz – Igloo di Giap

Mimmo Paladino – Elmo (1998)

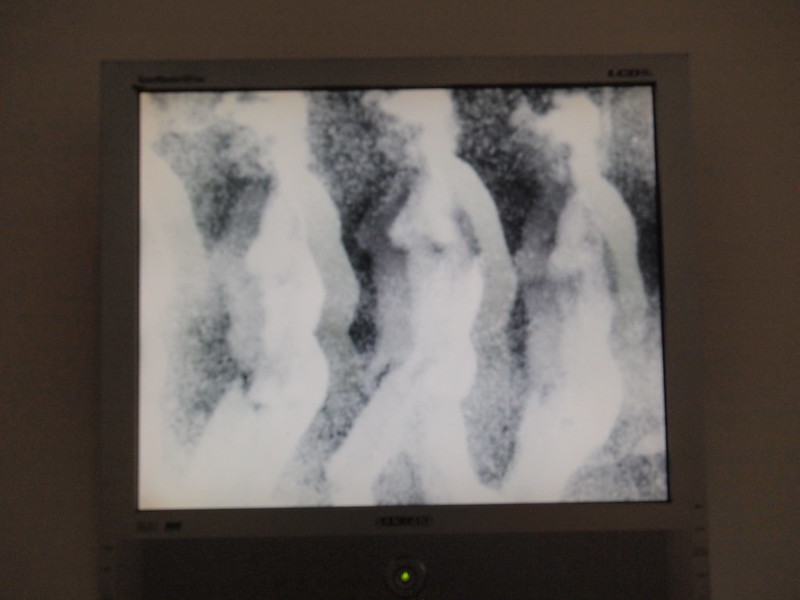

Paolo Gioli – Piccolo film decomposto (1986)

Alighiero Boetti – Tutto (1997)

Detail from Alighiero Boetti – Tutto (1997)

Another Warhol

Cy Twombly, Sans titre, 2005

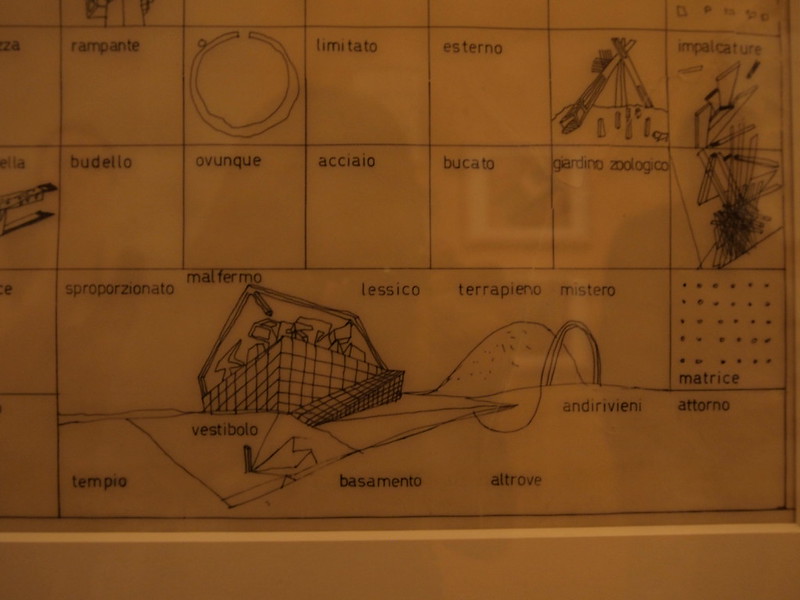

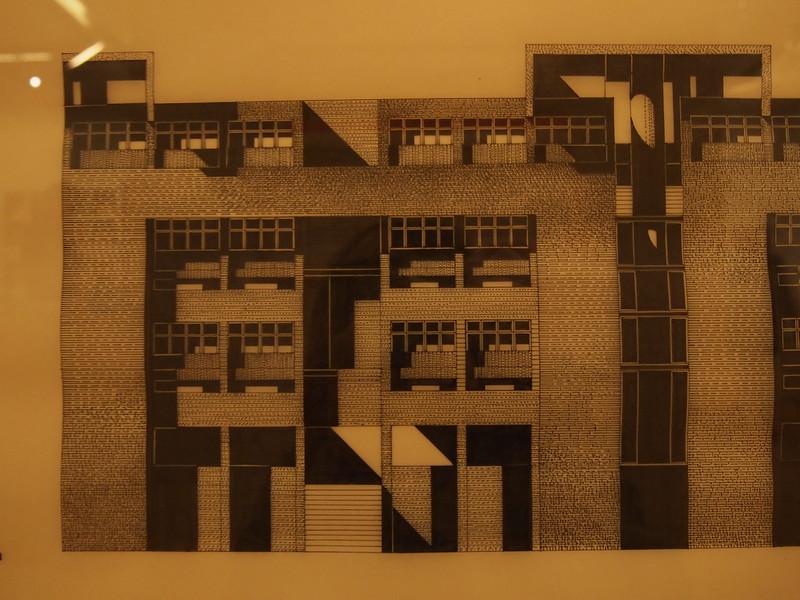

La Tendeza – Architectures Italiennes (1965-1983)

From the wall text: “La Tendenza is a name of a movement characterized by the intense debates that invigorated Italian architecture between the 1960s and the 1980s.”

By “invigorated”, I seem to get the feeling it could also be a euphemism for “pissing many people off after building some pretty radical-looking and alienating architecture.

Also from the wall text: “Opposed to the radical abstraction of the 1930s modernism, a number of architects sought constants in traditional forms of architecture and the city in an attempt to construct a new language, one which encouraged a new, more coherent culture to support the architectural project.”

This is a curious thing to write; to “encourage” or put together a coherent culture in order to support a project that has already been embarked on sounds like a rather shoddy excuse. Cultural reverse-engineering does not really sound like the right way to go about things really, but nonetheless from the position of one now looking back into the past, I still appreciated the attempt to put together a “typology” for architectures, and the spate of intense editorial activity and “manifesto exhibitions” which attempted to categorically rationalise the language of modern architectural design.

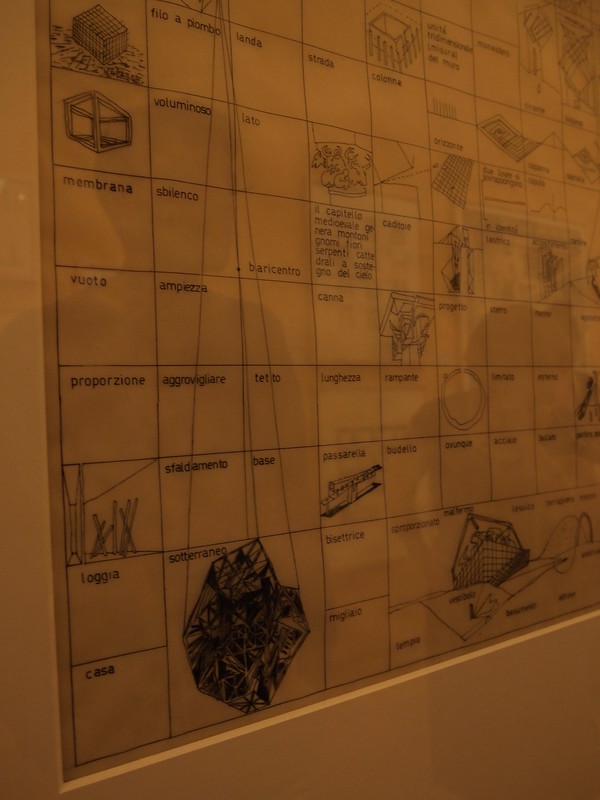

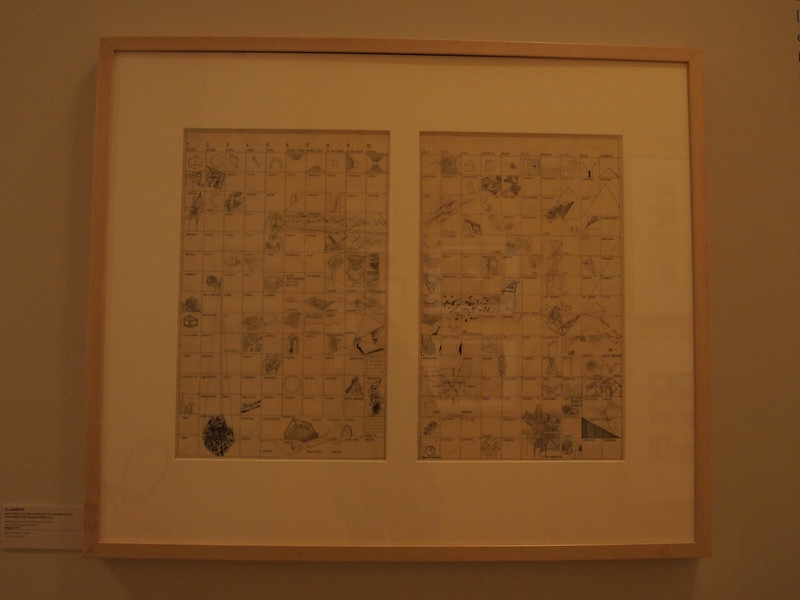

IL LABRINTO – Abaque (1975) – typology

Relations entre architecture et nature, formalisation, d’un nouveau langage architectural

Italian architecture – Laura Thermes