I’ve been in Canberra for two weeks now as an artist-in-residence with the Australian War Memorial; walking and exploring all around Canberra, as well as looking into its vast archives. Over the weekend, whilst looking around Google Maps for directions around Canberra I saw something very interesting…

The Changi Chapel.

THE CHANGI CHAPEL???

THE CHANGI CHAPEL IS IN CANBERRA

I was very puzzled: why hadn’t I heard that the original structure of the Changi Chapel was in Australia?…. Not once did I read in any book, pamphlet or material in Singapore that the “original” Changi Chapel was in Canberra! (and mind you, as a “completer-finisher” type of person, I thought I had read every single caption there was to read…)

Just a few weeks ago, me and Angela visited the replica of the Changi Chapel in Singapore, a simple and modest wooden chapel that sits within the courtyard of the Changi Museum. At the Changi Museum, the informational signboards do write clearly that it is a replica – but I have to admit that I blithely assumed we were seeing a replica because it had to be moved from its former Changi Prison site – and not because the original had been relocated elsewhere!

Outside the Changi Museum, Singapore

The Replica of the Changi Chapel inside the Changi Museum, Singapore

According to the Register of Significant Twentieth Century Architecture (by the Australian Institute of Architects), the Changi Chapel (RSTCA No: R055I) is a “rare surviving structure built by Allied prisoners of war from World War 2. A feature of the simple but refined chapel, which reflects the adverse circumstances of its construction, is the use of scrounged building materials.”

More from the Register of Significant Twentieth Century Architecture:

In October 1945 the War Graves Unit, including Corporal Max Lee, spent a few days by chance in the Changi Camp, en route to Sumatra. Corporal Lee made a request to the British to save the chapel, which was one of the few structures that had not been destroyed by fire. Permission was granted and after extensive photographs were taken and measured drawings and sketches were made by Lee, the Chapel was dismantled by a working party of surrendered Japanese personnel. It was crated to Australia in 1947, with the intention that the Chapel be reconstructed as a fitting memorial for “prisoners of war who had little recognition for the extreme adversity under which many had lived and died” (attributed to Lee).

The crates were stored in the Australian War Memorial where they remained for 40 years. The chapel was finally offered to the Australian Defence Force Academy and in 1987 reconstruction work commenced. The work was undertaken by the Royal Australian Engineer Corps. Following an unsuccessful application for Bicentennial funding, the Army launched a nation-wide public appeal for funds. In consultation with the Australian Heritage Commission, a site at Duntroon was chosen in the centre of small parkland close to the ANZAC Memorial Chapel.

It seems that I was confused because in 1988, two things occurred: (1) on the bicentenary year of Australia (1788-1988), the original Changi Chapel was reconstructed and dedicated as a National Memorial (to all Australian prisoners of war) in Duntroon, Canberra on the anniversary of the end of World War II (15 August 1945-15 August 1988), and (2) the replica of the Changi Chapel was constructed by the inmates of Changi Prison, as part of the Changi Museum built by the Singapore Tourism Board, situated outside of of the Changi Prison grounds. (The Changi Museum in Singapore was built in February 1988, according to this page containing research by Kevin Blackburn).

What a coincidence! Why was the Changi Chapel replica built in 1988 in the same year that the original was put back together in Duntroon? Was the decision to build the replica triggered by the reconstruction efforts of the original Changi Chapel over in Duntroon in 1988? Or of course a simple answer could be that 1988 was simply chosen precisely because of the significance of the year 1988 to Australian war veterans who would have wanted a memorial site to be constructed in Changi. But later again, the Changi Museum had to be moved because of the expansion of Changi Prison (as a prison for serious criminal offenders), so it was yet again moved to its present-day site at 1000 Upper Changi Rd North on 15 February 2001.

Standing on an area of 3.6m by 4.8m in Duntroon, the “original” Changi Chapel is clearly much larger than its “replica” in Changi – but then no one said it was going to be an exact replica. I suppose the main point is that there is indeed a transnational memorial at which people can come together to pay their respects and remember those who suffered or lost their lives during World War II.

I was thinking that another easy misconception to make if one just skims over all the material is that one might assume that the Changi Murals painted by Stanley Warren were in THAT original outdoor Changi Chapel, when actually the Changi Murals had been at the ground floor of Block 151 in Roberts Barracks – which had been converted into a chapel dedicated to St Luke the physician. I suppose its not very useful to call everything “Changi”, since Changi Gaol had been pretty large actually.

There had been 3 army barracks within Changi Gaol, namely Selarang Barracks, Kitchener Barracks, and Roberts Barracks. The Australians were sent to Selarang Barracks, and the British to Roberts Barracks and Kitchener Barracks. Roberts Barracks was later converted into Roberts Hospital. Stanley Warren was suffering from a severe renal disorder complicated by amoebic dysentery and was recovering in the dysentery wing of the hospital at Block 151, close to where St Luke’s Chapel was set up at, and he began painting the murals soon after the Selarang Barracks Incident.

This photograph taken during the Selarang Barracks Incident gives a sense of the sheer scale of Changi Gaol (which might come as a surprise to those unfamiliar with how huge it had been):

Photo Taken: September 1942

ID number: 042307

Description: Photograph taken during the Selarang Barracks Square Incident when Japanese General Fukuye concentrated 13350 British and 2050 Australian prisoners of war because of their refusal to sign a promise not to escape. The picture shows external excavations for latrines made necessary because of overcrowding in the barracks.

Source: Australian War Memorial

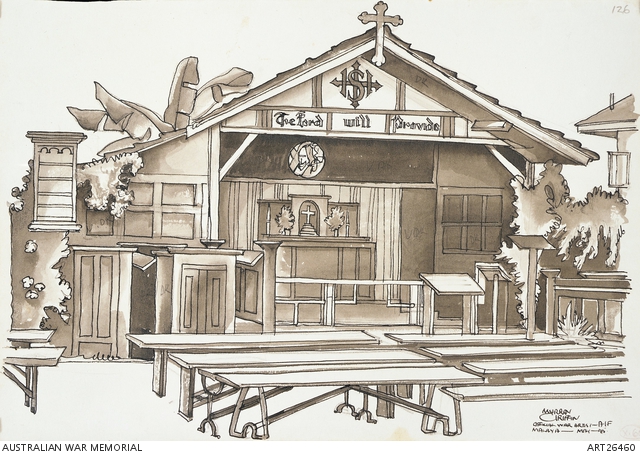

ID: 043124

Murray Griffin

Second World War, official war artist

St Andrew’s chapel

pen and ink and wash over pencil on paper

drawn in Changi, Singapore, in 1945

acquired under official war art scheme in 1946

ID: ART26460

Australia! You win at the collecting of Things! Not only do you have the Table, you somehow also have the Chapel too! But then again, I suppose that without the lobbying of Australian politicians, even the last bits of the original Changi prison wall would have probably disappeared (See also: ABC News (2004) – Singapore to preserve Changi prison wall)…

So the question that comes to my mind is… what is a country to do with a “transnational” memorial like the Changi Chapel – or Changi Gaol as a whole for that matter? If we think of World War II as a thread that has deeply entwined and shaped both Singapore’s and Australia’s individual histories and national identities, Changi Chapel and Changi Gaol is always going to be a part of Singapore’s history because it happened right here in Singapore, and as a former British Commonwealth army garrison and British Commonwealth PoW camp, it is deeply embedded in the memories of all of the 15,000 Australians soldiers who were forced into the PoW camp. Yet to describe it straight-up as a site of “shared memory” without any caveat seems wildly inaccurate; the Changi Gaol is really not a part of the Singaporean civilian’s personal wartime story. (also: I don’t know but can someone tell me what shorthand term I can use to call “the Singaporean” before WWII and before Singapore’s independence?).

I mean, before I began this residency I never even realised there was actually a whole thing, an entire pilgrimage tour wherein many British and Australians (war veterans/survivors/families of survivors/families of those who died in WWII) make this pilgrimage to visit the various WWII/PoW sites in Singapore… with the #1 site on the list being the replica of the Changi Chapel (in Singapore) which is confusingly not built to the original scale or design, and even twice removed from its original site!

The Changi Chapel in Duntroon, Canberra

It seems to me the Changi Chapel exists so vividly in the memories of the Australians to the point that the original has finally been brought back “home” and resurrected here in the nation’s capital, Canberra.(And perhaps that is why there has been no need for anyone in Singapore to mention that the original Changi Chapel is in Canberra…)

Also I should say at this point that I first saw the above images and photos in The Changi Book which I am reading right now. I could have slapped myself for not reading the whole Changi Book earlier – its big! and contains tons of stuff! and was seventy years in the making! – it has been amazingly edited by Lachlan Grant and contains the writings, drawings, paintings, and photographs created by prisoners of war in Changi – as well as lots of other essays by contributors from the Australian War Memorial. Many of those random questions I have asked out loud over the last few days have been answered in the book!

Eg: “Why was there a yeast production centre in Changi??”(Answer: Yeast contains vitamin B1 which was in short supply because of the POW diet of milled white rice which often resulted in vitamin B1 deficiency aka beri beri! So a yeast centre was built at Selarang to produce yeast from rice polishings, sweet potatoes, sugar and hops, which was then issued out to internees) “Then why did they knowingly build a rice mill and continue to polish all their white rice whilst in Changi?” (Answer: Because that was the only way they could get the rice to keep longer…)

On the issue of becoming obsessed with Rice whilst interned at the PoW camp: I don’t often like to quote the Daily Mail as a credible source of information but in this one respect I remember how they did carry a story about a couple who were both Changi Prisoners of War, Donald and Isobel Grist, and how Donald Grist “later became world authority on rice after becoming fascinated by how it could sustain humans for so long”. Reading the Changi Book I can now see why people became obsessed with food and rice. Grist’s name is also so apt, considering how the word GRIST refers to grain that has been separated from the chaff…

On the issue of becoming obsessed with food whilst interned at the PoW camp: IN THE NEXT POST…

Note: As I have a lot of notes to push out I’ll be backdating my posts to the approximate date of my visits to various sites and places, because I think it would be more useful to date my posts to when something happened rather than when I finished writing the posts in the random future… However, in case you are wondering, I did visit the Changi Chapel in Canberra today on 9 May 2017! And actually it is just a mere 9 minute drive from the Australian War Memorial!