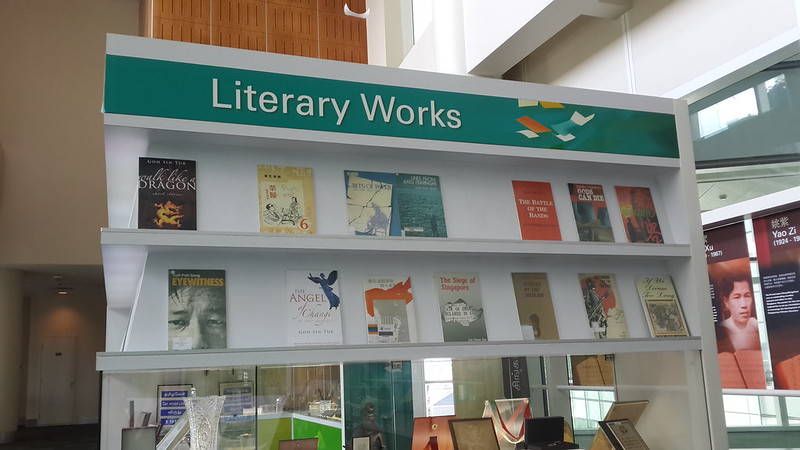

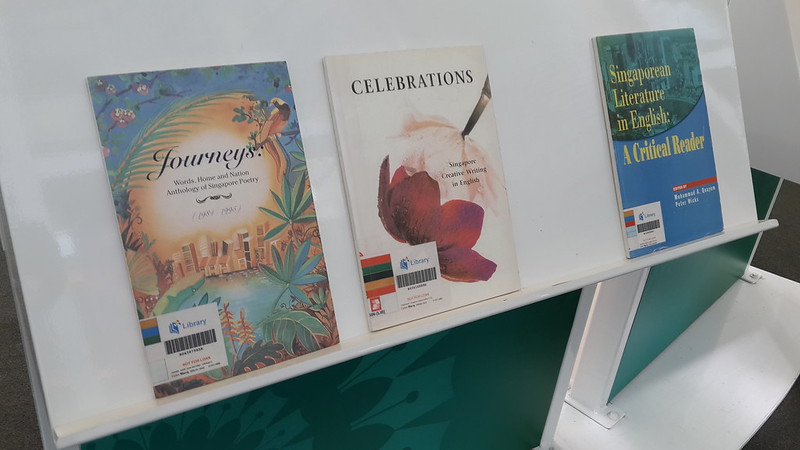

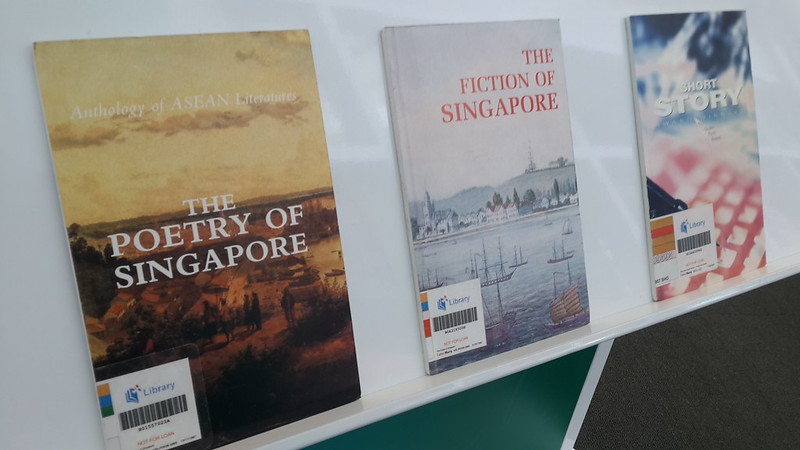

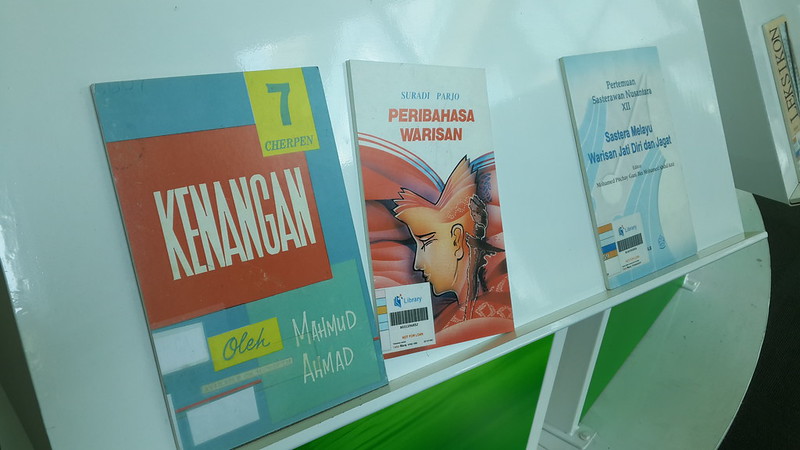

The other day I had a dream in which I wandered into a room and there was a white table with papers flying off into the sky. Behind it, there were shelves in which the books of all of Singapore’s literary pioneers were arranged, as if these books had been magically plucked out from the shelves of the library and lovingly collected into one room for our easy access…

Oh wait! I’m kidding, it wasn’t just a dream, it was real, and you don’t even need to wait a moment longer to experience the exact same thing in person if you’re in Singapore, for this very exhibition has actually been up at the National Library for the last ten years at Level 11. (Wait, what? Ten years??)

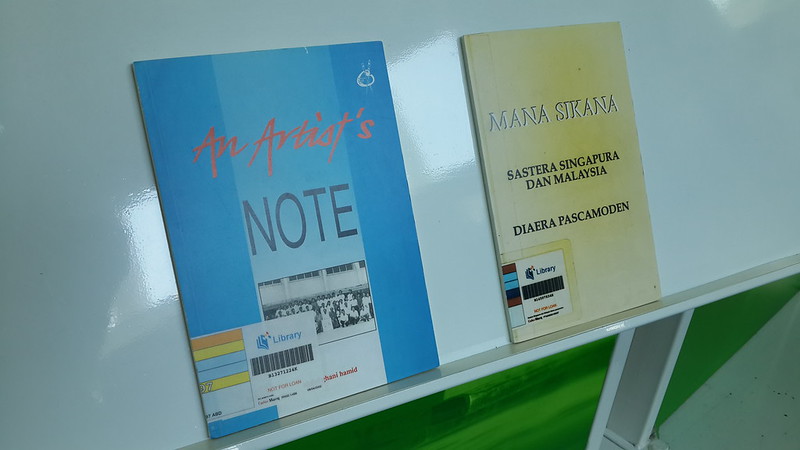

Some of the books on these shelves lay in a disarray, as if others had also picked them up and flipped through them recently before replacing them back onto these shelves. So I picked up a book…

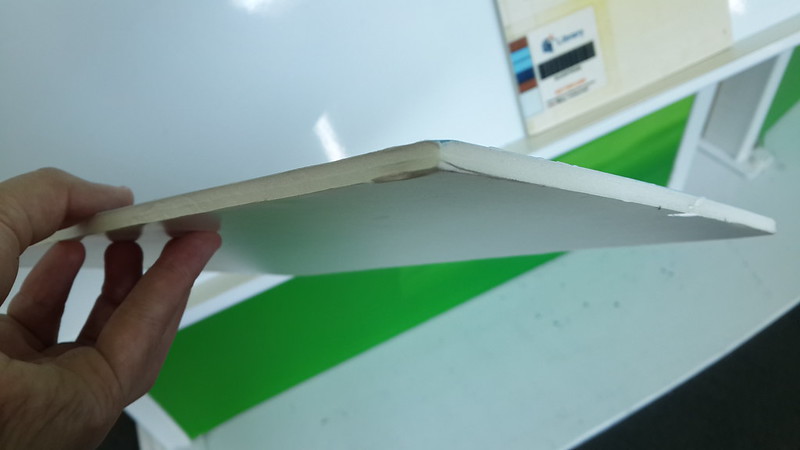

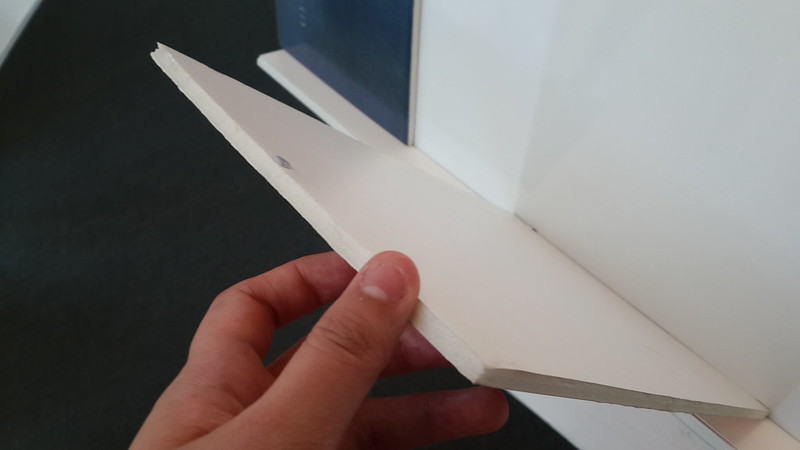

It was at that point that I realised it was not a book! It was just a solid block of foam with a scanned reproduction of the book cover printed on top of it! A bizarre Cronenburg-esque moment, all around me, what seemed like regular National Library books with the distinctively colour-coded stickers on their side turned out to be nothing more than hollow blocks of foam, devoid of words or detail on the inside!

Curious as to the origins of this exhibition, I looked it up and found records which show that the “Singapore Literary Pioneers” exhibition originally opened in November 2005, along with the National Library’s move to Victoria Street. Perhaps at some point during the past, these shelves in this exhibition actually held the original books, yet by this point they had all been put back into the collections, leaving nothing more than the skeletal, hollow foam board simulacrums of themselves behind…

The National Library has now been at its Victoria Street site for ten years now! Prior to that, the National Library had been at Stamford Road behind The Substation since 1958. In 1953 the rubber and pineapple king Lee Kong Chian donated a large sum to set up a national library which would be open to the public; in 1957 he laid the foundation stone for that iconic red-bricked building. But in 2000 it was announced that the building was to be demolished for the construction of a road tunnel and the new SMU campus. So the site of the former red-bricked NLB building unfortunately became a vehicular tunnel; a cruel twist which seemed almost emblematic of the denigration of people’s fondly remembered cultural spaces in the process of urban redevelopment – the library’s architectural and historical merits apparently insufficient for it to be have been gazetted as a national monument.

There was also a practical reason for the NLB’s move; I was reading the 1989 report of the advisory council on Culture and the Arts, which noted that book holdings in the National Library building in Stamford Road had already “exceeded the space available” – which was to the detriment of Singapore’s cultural development. So moving to a new building on Bras Basah would in theory allow for much more space – space for more collections, more books and more exhibitions.

I’ve graduated from RCA and I’m back in Singapore now! I have lots of things to document from the last few months (which I will document here in due course), but right now I’m working on something in September, on behalf of The Substation. I’ve been spending a lot of time at The Substation and the National Library building of late, constantly pondering the dilemma of writing text for an exhibition that is about an art space – but the exhibition will be held in a site other than its own – it will be at a library!

Mind you, I’ve also basically spent two years at a design programme being reminded that the gallery is not a library, and that the number of words in a gallery and museum should be kept as few as possible, because people came to look at things, not to read! But even now, when I’m preparing an exhibition to be set in the library, where the words should be more plentiful, where we shouldn’t need to be shy about shoving books in people’s faces, the caveat about not overwhelming the reader/viewer with too many words still exists.

I wonder, if that is why there aren’t words inside the books in the Level 11 exhibition? Would the presence of so many words in the space make everyone less likely to engage with the content fully? Perhaps it was feared that putting the actual books on show would induce viewers to get stuck at the first book they came upon, rather than skimming through this condensed history of Singapore’s literary landscape.

Maybe this is a matter of exhibition design. Let’s talk about in numbers, since most Singaporeans seem to understand things better in terms of numbers. How many words can we realistically hope that the average person will read at an exhibition? The average reading speed of a native English language speaker is said to be between 250 to 300 words per minute. Let’s give it a bit of wiggle room and assume that the bilingual Singaporean (in a moment of idle distraction!) reads only 200 words per minute.

If an average visitor spends half an hour in our exhibition space, but only spends 50% of his or her time actually reading the text on the wall (the other 50% being spent on talking to people, looking at the pretty pictures, looking out of the window at the skyline, or watching the videos), then perhaps we can hope for 15 minutes x 200 words or about 3000 words to be consumed during an average visitor’s half-hour long trip to an exhibition – if we are so lucky!

This means that if I write more than 300 words for each of the 10 sections of the exhibition, then maybe most people won’t be able to read everything I’ve written in an average visit to the exhibition.

But how can I possibly tell you the 25 year history of The Substation within 3000 words – scarcely more than an essay’s length? Would it be better if I put more shiny pictures on blocks of hollow foam? But the photos are so few. And all I have are so many of these texts, quotes, paraphrased rumours, and snippets – surely this amounts to more and more words being packed into the show!

But maybe the most important thing is not just the big, beautiful, totalising statement that will sum up everything within my 300 word count. The things I want to tell you come in the form of almost insignificant details. Maybe there isn’t anything metaphorical about it.

I’d like to believe that what seems like textual fluff, the description of events and people and programmes and objects and their seeming insignificance in relation to the larger narrative, actually is key to our understanding of it. In his essay The Reality Effect, Barthes argues that these small insignificant details, when put together, signify the real, the l’effet de reel.

For me, there is something so important about all these insignificant, longwinded details. In La Nuit des prolétaires: Archives du rêve ouvrier (which was published in English as “Nights of Labor”, or “Proletarian Nights: The Workers’ Dream in Nineteenth-Century France”), Rancière presents a series of fragmentary, seemingly insignificant details and contradictory accounts of a small group of worker-intellectuals in the 1830s and 1840s. I like his seemingly anti-sociology, anti-historicising approach in digging through the archives to excavate these accounts. In the introduction, Rancière writes:

If the protests of the workplace are to have a voice, if worker emancipation is to possess a human face, if workers are to exist as subjects of a collective discourse which gives meaning to their multifarious assemblies and combats, those representatives must already have made themselves other in a double, hopeless rejection, refusing both to live like workers and to talk like the bourgeoisie.

This is the history of isolated utterances, and of an impossible act of self-identification at the very root of those great discourses in which the voice of the proletariat as a whole can be heard. It is a story of semblances and simulacra which lovers of the masses have tirelessly tried to cover up.

The night forms the grey area where poor workers unexpectedly double up as clandestine intellectuals; Rancière chooses to give significance to quotes from hybrid figures, painting a much more incongruous picture of the digressions, distractions and conflicting motivations behind each individual that is often taken to be part of a whole, giving significance to the words and stories which could have easily dismissed as meaningless since they were hard for us to process or to summarise into a ‘pure’ or neat theory.

In choosing to structure an exhibition around “spaces”, I feel that the goal of my role as ‘curator’ or ‘mediator’ of the archive would be to position these hundreds of extracts from the Substation’s archive in a space between a conventional confinement to their “place” in time and space – and a completely utopian or metaphorical abstraction of the spaces…

One response to “In Praise of Insignificant Details”

I assume this one is not part of the exhibit: http://www.complete-review.com/reviews/singapore/mohamedml.htm