1. TURING TERMINOLOGIES

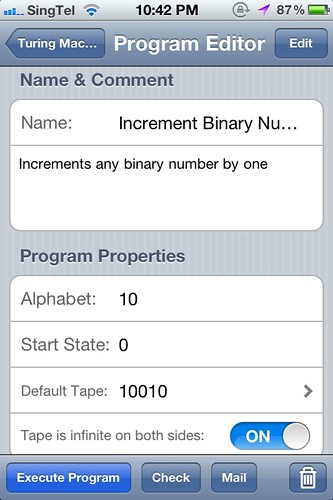

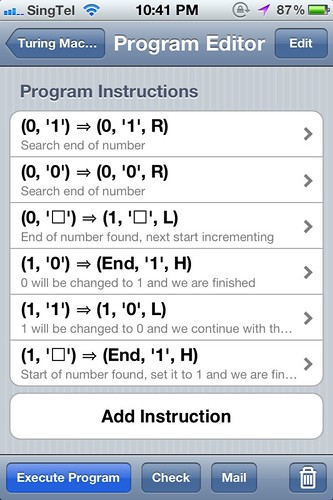

Incremental binary number turing program

Recently, I have been rather fascinated by the terms or keywords associated with the various functions of the Turing Machine, “a theoretical computing machine invented by Alan Turing (1937) to serve as an idealized model for mathematical calculation”.

It was the first “theorectical” computer to be made up (on paper) and in its simplest form, it would consist of a tape of indefinite length and a head which can move the tape and also write more symbols to the tape. The head would read the symbol and would choose to write a new symbol in place and then move either left or right.

The Turing Machine also runs a program. The program is a list of instructions – it determines how the machine should run depending on what state, what symbol is under the head, and what should be written next on this tape, and which state the machine will subsequently go to, and whether the head moves right or left.

I downloaded an iphone application which simulates a Turing Machine. You can write your own programs and test the mout, and the application also comes with some default programs as well. It makes a pretty good game to play as well, if these kinds of logic puzzles amuse you. If it were more visually exciting I would probably play it all the time (but for more algorithimic fun, ContextFree is most excellent too…)

Some of the associated keywords (on the Wolfram Mathematica site) look like this:

Abstract Machine, Automata Theory, Automatic Set, Busy Beaver, Cellular Automaton, Chaitin’s Omega, Church-Turing Thesis, Computable Number, Deterministic, Halting Problem, Langton’s Ant, Mobile Automaton, Nondeterministic Turing Machine, Register Machine, Turmite, Universal Turing Machine

It is amazing how looking more at mathematics also turns me back towards a desire to write more and more. [And in a similar vein, I also recently acquired a copy of Kostas Terzidiz’s Algorithmic Architecture! How strange that getting deeper and deeper into computing and programming can also make me feel more and more connected to all the things outside of the computer…]

2. DOGTOOTH

Last week we watched Yorgos Lanthimos’s Dogtooth (2010). I had searched for a recommendation in the format of “Similar to

Dogtooth is one of those films that will most certainly be adored by those who have an obsession with words. An unusual, surrealistic film that portrays a family with three grown children who have been kept without contact with the outside world, the film opens with a tape playing back words like a language vocabulary teaching tape, except that the words are all read back wrongly. The children are able to speak like normal people, with the exception of being a little stilted, and their father being able to command them to do the strangest things, like to get on all fours and bark like a dog to protect the house from supposed enemies, and for them to say things which sound utterly bizarre to us. In this respect, it is so far from the norm of reality that it becomes almost science fiction. Social engineering in science fiction, to be precise.

Despite being a film that only looks inwards, I think it is a very relevant film as it has managed to capture two issues very perfectly – that of the tyranny of the family and the household, and the failure of modern communication. Of what happens when you try to control people by having them believe what you tell them. It extracts out the inherent lies and what lies bare are the words: What we see on the news and in the streets are all made up of words; who says these words have to be true? What are words anyway? When the very meaning of words has been undermined, what happens to the order of things?

The result is that Dogtooth paints a picture-perfect portrait of what appears to be society’s idea of normalcy at first glance, but slowly sheds and breaks the family’s routines to reveal the horrors beneath the surface of communication and modern existence.

The children in the film are obviously invented characters put in a situation that has been painted as being quite extreme, and in their isolation, they are portrayed as rather flat and seemingly without much depth. However, far from feeling detached from that portrayal, I actually really enjoyed the film and felt very much for the children in particular because as an only child I did have episodes of sitting around alone, feeling similarly flat and oddly without depth, like a blank cipher. At the age of 10 I remember that I was keenly aware of my conscious existence and this made me really frustrated with my seeming blankness or “lack of a character” – so I actually went and arbitrarily invented for myself a “favourite colour” (I randomly picked green and actually tried very hard to psyche myself into liking it), a “favourite number” (I picked 5 but I don’t know why), and other things like that. It was because I was so bored with having to tell grownups and other people that I didn’t really have a preference for anything at all.

I also recall making up games like “Lying Flat on the Floor For Hours and Moving So Slowly Across It That No One Notices That I’m Actually Purposefully Moving Across The Room”. Perhaps, not so much unlike the girls and their game with some anesthetics, in which the Youngest one says to the Eldest, “I have a new anesthetic. Let’s play a game: the one who wakes up first wins…”

I guess I just had a lot of time alone with myself, wondering to myself why people invented structures that we assumed were normal like “families” and “societal expectations” and “cultural habits”. It wasn’t a bad childhood by any means, but maybe a wee bit isolated so I ended up making up lots of funny stories in my head and then wondering why the big performance of real life had to be written with all these preconceived roles and rules.

3. WALLED CITY

In a similar vein, I think I would like to write a novel about a building, but not in a conventional novel format. I already know which building I want to write about. This building is very far away but very fascinating in that, like Dogtooth, it reminds me of a walled city.

Yesterday I came across Franco Moretti’s Abstract Models for a Literary History, which argues for more mapping and graphing in Literary Historiography and a more experimental approach to literature (of which, the form of the novel has stagnated for far too many years!). It appears to have a healthy study of the various genres and novelistic forms that have had mass acceptance or popularity over the years. This book also begins with the following epigraph, which is also the exact same question that I find myself asking:

“A man who wants the truth becomes a scientist; a man who wants to give free play to his subjectivity may become a writer; but what should a man do who wants something inbetween?”

– Robert Musil, The Man without Qualities