“Sub-monument visualises the art space as a signal processor which removes or amplifies specific features of the received signal to generate various artistic manifestations. For the art space to keep on running, this absurdist hardware requires a physical building and constant upkeep from its devoted programmers – the hybrid artist-programmers who translate and parse source material into shamanic code and thaumaturgical scripts inscribed upon oracle bone – in order to resurrect uncanny cultural apparitions from the years before, invoking an eternal cycle of audience and practitioner sighs.”

“[Monuments] speak on your behalf, they require your symbolic death.”

– from Janadas Devan’s “Is Art Necessary” (Art Vs. Art: Conflict & Convergence: the Substation Conference, 1993. Singapore: The Substation, 1995)

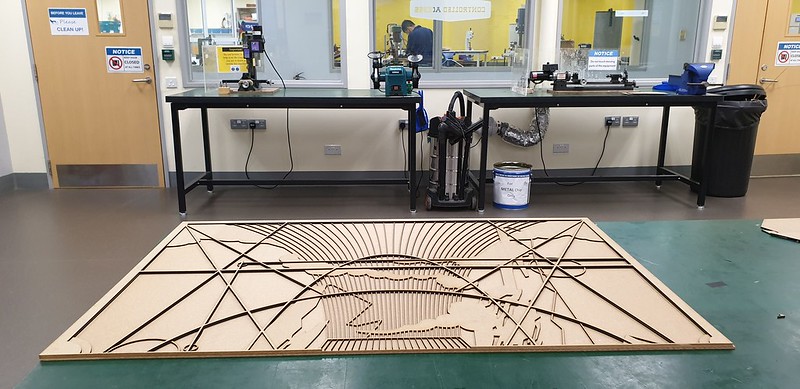

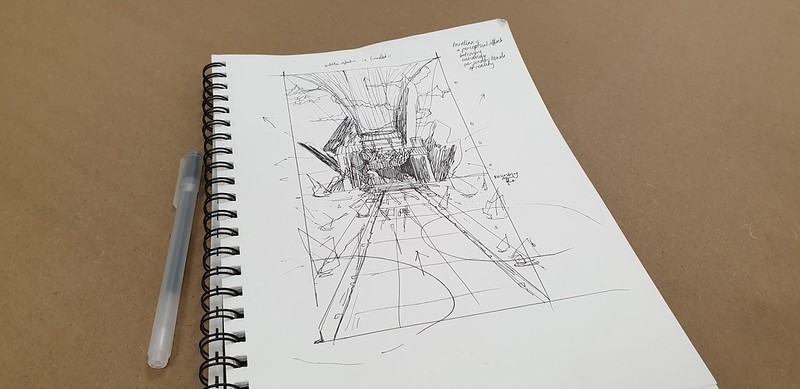

About a year ago I agreed to work on a show in 2019. THEN A YEAR FLEW BY. AND ALL OF A SUDDEN THAT TIME HAD COME WITHOUT ME REALISING! So… I had to quickly produce the work during my (fortuitously timed) week off from work. I already knew from the start that I wanted to produce a large woodcut using lasercut because I had access to an awesome lasercutter of considerable size, and I imagined it to be a cross between an architectural drawing, blueprint schematic and alchemical scroll…

I wanted to make a mysterious diagram, depicting an arts centre as a kind of haunted machine, or diabolical signal processing hardware; a machine into which all the ideas and intentions of the artists and arts programmers and artistic director trickled into… or maybe not so gently. Maybe the energies of all these artists and programmers and art workers were being uncontrollably sucked up into, brutally chewed up, and then this big machine spat it all out as art, scattering it randomly into the sky, broadcasting it far and wide, without total control on how it rained down or haphazardly drizzled upon the audiences.

What keeps the arts centre runnning? What kept the artists going? Where did they come from? How was it that there were always new generations of artists and programmers returning to feed it and keep it going? Was it simply the insatiable hunger of the arts machine demanding to be fed more fodder? And as time wore on, I want you to imagine the frightful sounds of the wear and tear on the various essential parts of this strange hardware: the groaning from the repetitive motion of gears, and the creaks from all the pressures of delivering this non-stop service, the echoes of lost voices within this highly emotional social space…

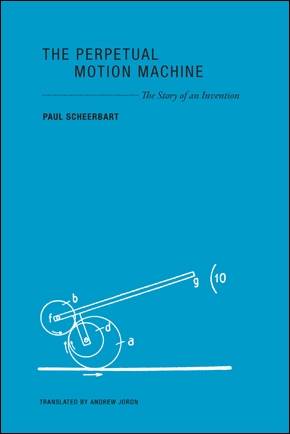

One of my favourite books is a very slim volume – Paul Scheerbart’s The Perpetual Motion Machine: A Story of an Invention, wherein he documents two and a half years of his life which he dedicated to his foolhardy attempts to build a perpetual motion machine, complete with 26 illustrations of his prototypes and accounts of his building process, accompanied by countless grandiose digressions into the potential futures he imagined that would follow after he had finally invented a working perpetual motion machine.

His apparent lack of experience/aptitude for physics and most forms of mechanical or practical engineering seemed to be of no deterrent to him, and he approached the challenge of constructing and designing a perpetual motion machine with a kind of fanatical enthusiasm and earnestness that might be read as either sheer genius or complete idiocy. Perhaps what had induced Scheerbart’s literary prolificness (and his endless tinkering) was the fact that then whenever he met with technical difficulties, he would allow himself to mentally leap over all these impediments and go straight to dreaming up fantastical futures with his perpetual motion machine.

Naturally, one may make one’s own conclusions as to which arts centre I am thinking of. It is a very beloved space indeed, yet one that surely many artists in Singapore have conflicting feelings about. This isn’t even the first work I’ve made about it. Does my illustration or mapping of this schematic change anything about how the future will run? I’m afraid not at all. But I am still driven to make something at the end of the day; it unexpectedly surfaces like a recurring motif in a dream.

Production Process

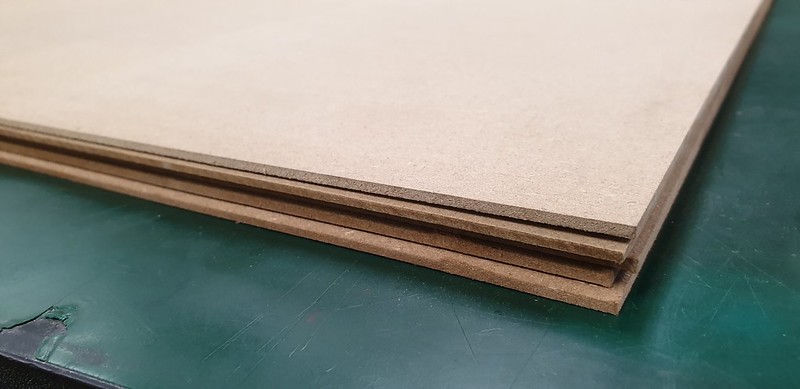

On the practical front, Artfriend sells 35 x 24 in. MDF (approx 910mm x 600mm) which is suitable for the GLS Spirit Laserpro which I had access to. The Spirit has a normal cutting bed of 34 x 24 in. (860 x 610 mm) which can also be extended to 38 x 24 in. (960 x 610 mm). [In the print settings you may need to tick the option “Extend” to get the larger size]

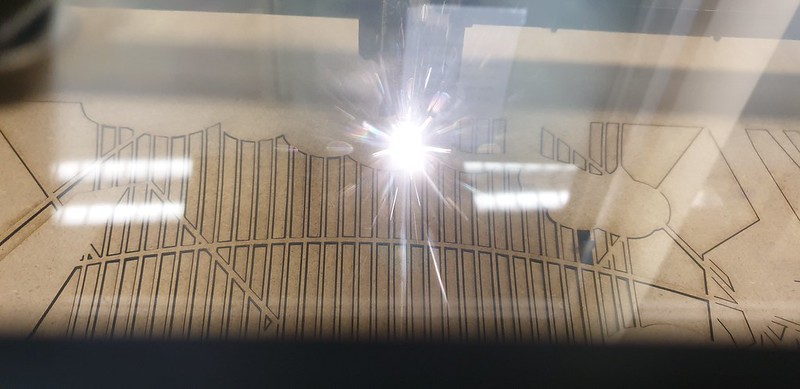

Issues encountered when Laser-cutting large works:

If the line is not perfectly crisp, you should pause and relevel the machine!

Some of the lines above were cut twice hence the severe burn as well…

1. Bed or material is not perfectly flat: I do find that with such a large cutting bed there is a tendency for some warp-age which means that you have to level it several times to get an “average” level otherwise either the edges or the centre will be out of focus. Pat material down totally flat and make sure there are no stray bits of nobbly fragments pushing any corners of the wood up. If there is a focus problem, the “burn” will be more diffuse, you’ll produce a smoky line instead of a sharp cut.

2. Material may not be uniformly thick. The first few pieces I cut were perfect but then I noticed that one of the pieces of wood was a different colour, probably from a different batch, with slight variance. And unfortunately, not all wood is the same. Measure it with callipers or just do it the simple way: lay all out the material side by side on a flat table and compare to see which one is slightly thicker. In my case I found that the offending sheet that gave me trouble was more like 3.2mm than 3mm!!!!). For me, I’d say the quick fix is to cut it with a thicker wood setting (eg: 5mm). If you try to cut over an already cut piece of wood, you’ll cause a lot of burning and charcoal on the finishing as the cut edges burn for a second time.

I had to switch the cutting profile from 3mm plywood to 5mm plywood in order for it to successfully cut on the first pass.

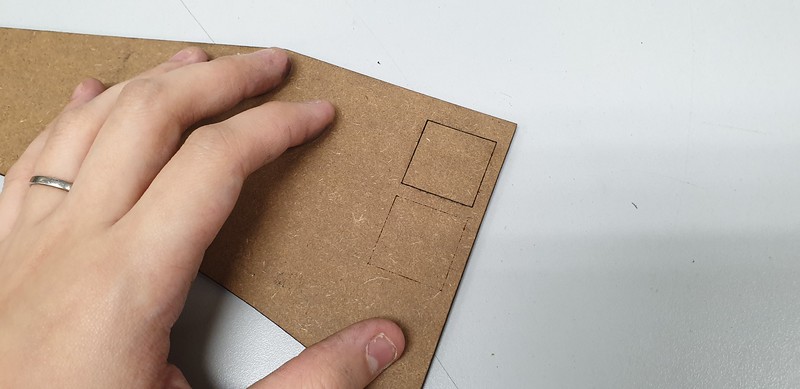

This is what it looks like on the back of that experiment – and what it looks like when it hasn’t cut fully through.

3. Excessive Burning on out of focus areas: If your first cut didn’t work because it was out of focus, it may have seemed logical to put it thru a second pass. However, the cut becomes more and more sooty and dirty, as if more of the edge has burnt off! However, reassuringly, I found that you can still sand off the burns entirely if you still wish – it hasn’t all turned to charcoal!

Bachelorette machines

Artists: Debbie Ding, Goh Abigail, Vanessa Lim Shu Yi, Victoria Tan

Curator: Caterina Riva

Bachelorette machines brings together works by four Singaporean artists: Debbie Ding, Vanessa Lim Shu Yi, and LASALLE BA(Hons) Fine Arts alumni Goh Abigail and Victoria Tan. Inspired by the artistic concept of the bachelor machine, the exhibition highlights the ideas and physical labour of these artists’ works.

In 1913, avant-garde artist Marcel Duchamp made a reference to the bachelor machine as a jumble of mechanical implements and schematic diagrams. In the exhibition, the bachelor of this art-historical definition becomes the ‘bachelorette’, echoing the song written and released by Björk in 1997.

In the exhibition, the machine conveys the historical and imagined engineering tools which have inspired these four artists. Spanning Praxis Space and Project Space, the exhibition includes sketches and installations, offering different entry points into the artists’ working processes.

Goh Abigail explores sound through a series of automated sculptures and drawings. Made of ordinary materials and objects, Vanessa Lim Shu Yi’s system of perpetual motion is designed to stimulate the human senses and muscles. In a new series of screenprints, Victoria Tan captures the changing landscapes of temporary sites in Singapore. Debbie Ding presents a prototype of an arts space as a processor, which filters analogue signals in order to generate various artistic outputs.

Opens on 4th April 2019!

Date & Time:

Opening date: Thu 4 Apr 2019, 6:30pm-8:30pm

Exhibition period: Fri 5 Apr – Sun 5 May 2019

Opening hours: 12:00pm – 7:00pm, Tue to Sun (Closed on Mon and public holidays)

Location:

Praxis Space and Project Space

Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore

LASALLE, 1 McNally Street